Varied and fantastic tales proliferated not only in romantic works of fiction such those we encountered in our last lecture, but also in medieval retellings of the Roman poet Virgil. These editions took significant departures from the biographical details of his life lived in antiquity (70 – 19 B.C.E.) and incorporated fantastic qualities which mirrored the taste of the composers of medieval Romantic stories. As with the proliferation of a “techno-mythology” of the latter, we a similar narrative about the manufacture of automata work its way into the Virgilian legends that appeared in the Medieval period.

This tradition began as a phenomenon of French and Anglo-Norman clerical writers from the mid-twelfth century that inflated the reputation of Virgil as a magus or sorcerer. Policratus, written ca. 1159 by John of Salisbury, called him the “Mantuan seer,” and subsequent versions mirror the demonological automata described in secular chansons de geste like Aymeri de Narbonne or Lancelot do lac; a tradition appears in some versions that Virgil’s powers were given by twelve demons that he released from a bottle.

Introduced in this early text is the legend that Virgil created a cast-bronze fly that guarded the city of Naples, preventing any other fly from entering. Here we see a vestige of the very-historical tradition from Eastern contexts of creating a cast-bronze vessel of an animal which had apotropaic and protective benefits for the city or kingdom. The pre-Islamic copper lions and eagles at the Himyarite palace of Ghamdan and later the hollow eagles at the four gates of Baghdad embody this antique practice, and the medieval Islamic cast-bronze animals like the Pisa Griffin and Mare-Cha Lion are examples of the kinds of transitional objects being assimililated by the Latin West. Carolingian and Ottonian centers of bronze production had made their own versions of the large-scale brazen lion and other types well before John of Salisbury’s time, and we have seen how the process of manufacturing metal objects to trap and emit celestial influences as laid out by Al-Kindi, Thabit ibn Qurra, and others circulated widely in Europe as well. This is the context then, for the proliferation of this legend of Virgil’s bronze fly which was repeated in at least four instances before the end of the twelfth century. Conrad of Querfurt (ca. 1160-1202), Bishop of Hildesheim and the tutor to Emperor Henry IV described the fly in a letter dated 1194 to the monastery of Hildesheim:

“In the same place there is a gate, built like a fortress with bronze doors guarded now by imperial guards, where Virgil placed a bronze fly, and as long as it’s in place, not even one fly can enter the city.”

The historian Ittai Weinryb’s The Bronze Object in the Middle Ages recognizes the bronze fly’s operation as one based on the principle of similia de similibus, “like affects like,” and connects it as well to the age’s tradition of apotropaic talisman manufacture. A ca. 1460 illustration by the Juvenal des Ursins group for the Livre des merveilles presently held and digitized by the Pierpont Morgan Library, features a large cloud of flies ostensibly held at bay by the bronze fly constructed by the philosopher while a trumpet-blowing automaton repulses the ash from an erupting Mount Vesuvius with the wind he generates, to which we will return shortly.

Already in the span of about thirty years which separate John of Salisbury’s letter from Conrad of Querfort’s, we find the addition of another distinct element in the latter: a bronze horse manufactured by Virgil that makes the other horses run faster. Weinryb has sourced this particular iteration of the cast-bronze-animal-as-talisman in the writing of the sixth-century Byzantine John of Malalas, who furnishes an account of the miraculous bronze horse made by Apollodorus of Tyana for the Constantinople Hippodrome. The abilities of this prototype differed in scope from Virgil’s in Conrad’s letter: the Constantinople horse, which finds mention in the later ninth-century writings of Harun ibn Yahya, prevented live horses from making noise as they passed through the capital.

Another novel aspect of Conrad’s description is the aspect of the magically-guarded tomb which might bring up associatons with the chambre de beautés of Hector or the tomb of the Amazon Camilla in medieval romantic literature surveyed in our last lecture. Conrad’s description of the fly previously quoted continues:

“In the same place, in a nearby castle at the summit of the city surrounded by the sea, there are the bones of Virgil, and if someone exposes them, the entire bronze face [of the sea] will darken, the sea will burst from its abyss in racketing storms. This we saw and confirmed.”

With the accretion of legends about his supernatural powers, came a status usually reserved for Christian saints; Virgil’s bones were believed to protect Naples, the city of his life and tomb. Nor was this an isolated case; the philosopher Livy’s arm bone was a gift from the Venetians to Alfonso the Great of Aragon and was received with solemn pomp to the city of Naples as well. One historian observed of this peculiar case, “…how strangely Christian and pagan sentiment must have burned in his (Alfonso’s) heart!” By the Middle Ages, any trace of human remains had been removed from the tomb traditionally assigned to Virgil adjacent to modern Naples. By the eighteenth century however, it had become a popular subject for the Romantic painter Joseph Wright of Derby. The ability to conjure storms by various methods can be located in contemporary medieval and Byzantine literature as well, such as the act of pouring water from a particular fountain in order to produce a magical storm recounted by Chrétien de Troyes. The conjuring of a storm by magicians at the Byzantine emperor’s court is witnessed by Girard de Rousillon, and the bronze boys that smile at one another in the Palace of Constantinople when wind blows in from the sea described in the Pèlegrinage de Charlemagne may be a sincere account of the automata included above among the documented automata of Byzantine emperors. Other medieval versions of Virgilian legends recounted how Virgil’s magical-mechanical genius would have even granted him immortality, if it were not for the meddling of an ignorant character. In one version, it is a king: Virgil instructs a servant to chop up his body after death and pack the pieces in salt for nine days, after which he will be rejuvenated, Osiris-like, and a mechanical automaton is put in action to guard this arrangement. However, on the seventh day, the emperor, missing his friend the poet, destroys the automaton and interrupts the process, sealing Virgil’s mortal fate. In another version, it is the apostle Paul who disturbs Virgil’s automated sepulcher; there is no resurrection ritual underway, however. St. Paul sees only the uncorrupted body but is blocked by an automatic mechanism with flails. When the machine is deactivated, everything that St. Paul sees- the body, the books, the automaton, etc.- crumbles to dust.

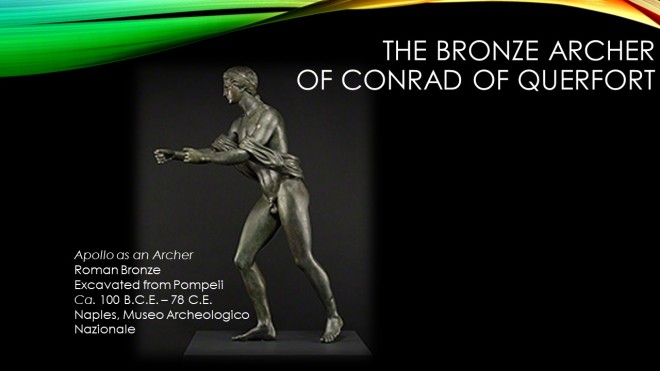

Finally, the last novel feature of Conrad’s account is a bronze archer- perhaps iconographically similar to the Apollo excavated from Pompeii (see http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/apollo_pompeii/g)- that faced Mount Vesuvius and prevented its eruption until, according to the same archer, an idiot caused the statue to loose its arrow. That arrow found its mark on the side of the volcano, which caused it to begin erupting again. Here too we find the trace of the guardian-automata of the tomb, repurposed here to address the specific threat to Naples and her people.

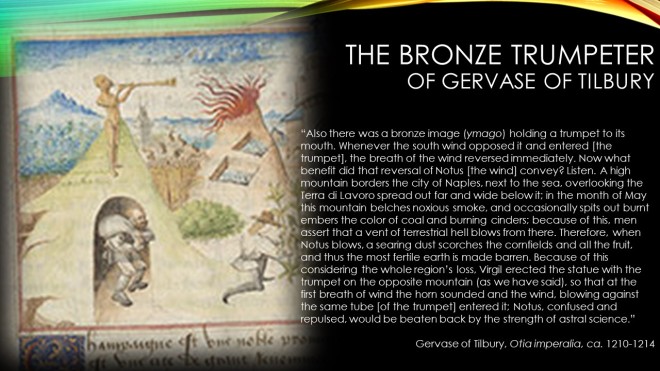

This convention of an automaton safeguarding the Medieval urban community appears in a slightly modified form in the marvels listed in the Otia imperalia written by Gervase of Tilbury (ca. 1150 – ca. 1228) around 1215. The description ends with an explicit attribution of the work however to astral science, rather than demonic magic:

“Also there was a bronze image (ymago) holding a trumpet to its mouth. Whenever the south wind opposed it and entered [the trumpet], the breath of the wind reversed immediately. Now what benefit did that reversal of Notus [the wind] convey? Listen. A high mountain borders the city of Naples, next to the sea, overlooking the Terra di Lavoro spread out far and wide below it; in the month of May this mountain belches noxious smoke, and occasionally spits out burnt embers the color of coal and burning cinders; because of this, men assert that a vent of terrestrial hell blows from there. Therefore, when Notus blows, a searing dust scorches the cornfields and all the fruit, and thus the most fertile earth is made barren. Because of this considering the whole region’s loss, Virgil erected the statue with the trumpet on the opposite mountain (as we have said), so that at the first breath of wind the horn sounded and the wind, blowing against the same tube [of the trumpet] entered it; Notus, confused and repulsed, would be beaten back by the strength of astral science.”

However, the slightly earlier account of Alexander Neckham of the Virgilian legend in his De natura rerum (ca. 1190s) furnishes a greater panoply of mechanical and medicinal marvels that are outside the traditions of John of Salisbury, Conrad of Querfort, and Gervase of Tilbury. These included neutralizing poisonous leeches by the use of a gold leech (which echoes the operation of the bronze fly legend), making a combination of herbs to be hung at the butchers’ stalls that kept meat fresh for five hundred years, and the making of a bridge from air that took Virgil wherever he wanted to go. Chief among Neckham’s elaborate wonders was the Salvacio Romae, a collection of wooden statues housed in Virgil’s palace in Rome that corresponded to each imperial province When any of these provinces were being threatened, another statue representing the Roman Empire would ring a bell, causing a brass horseman to mount a pediment and turn in the direction of the rebellion, so that the Emperor might know where to send his real troops. Neckham gave a characteristically Medieval Latin expiration date to this wonder of antiquity; when asked how long the automata would endure, Virgil responded, “Until a virgin shall bear a child,” which, according to the Christian calendar, was only a few years after the Roman poet’s death.

These twelfth- and thirteenth-century inventions themselves belong somewhere between the automata of fantasy and fact. Their themes are not strictly locatable within the historical Classical legacy, yet they perpetuate many ideas about what could be possible from antiquity in Western European Medieval civilization. In this sense, it has been observed that the Virgilian “techno-myths” at times appear identical to the marvels performed by Apollonius of Tyana at Constantinople. Still further duplications of elements of the Apollonian/Virgilian marvels appear farther east in Indian literature and beyond. Some literary influence may be admitted, but historians of automata and magic alike are in agreement that the “wizardization” of the Roman poet Virgil was a medieval phenomenon, possibly due to his status as a great pagan mind and the fact that he came from a culture testified primarily in this time by mute, life-like ruined statues. Virgilian legend-making persisted for a span of centuries, and reports of a medieval Bishop of Naples, Virgilius, belong to this genre. The historian Silvio Bedini perceives in the Virgilius figure an amalgamation of brilliant pagan personalities, the poet Publius Virgilius Maro to be sure, Hero of Alexandria, and folkloric magic, in a Christian persona. Even more automata are attributed to this medieval incarnation, including the large brass fly which chased away the others and kept the city’s meat preserved for eight years. However, the phenomenon in medieval culture, which oversaw the transformation in popular perception of the Roman poet Virgil to master-inventor to magical adept to, in some stories, servant of the devil, was a reputation destined to be applied to contemporary intellectuals as it was to the great figures from the pagan past.