This survey of a selection of the religious structures, customs, and beliefs on the Arabian Peninsula from the Bronze Age through the advent of Islam by necessity of length is bound to restrict its analysis to a broad differentiation of the civilizations and peoples between a split that occurred sometime in the Neolithic: between those groups whose existence remained nomadic and pastoral, the itinerant tribes recognizable in the Bedouin of the present day whose rhythms of life are tied to the movement of their flocks, and those which mirrored the rise of Sumer and the Mesopotamian empires to the north with the mastery of agriculture, irrigation achieved by the diversion of predictable, seasonal floods, the building of walled cities, monumental temples, and a unique system of writing; these latter are the Qataban, Ma’in, Hadhramawt, and, most prominent of all, Saba (Biblical Sheba) concentrated in the southwestern corner of Arabia in modern-day Yemen. With the Islamification of the Peninsula in the seventh century, after the Sabaean kingdom and the overland trade route of antiquity had given way to the Himyarite Empire and the thriving sea-trade with its connections spanning the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean, a deliberate campaign of religious iconoclasm erased much of the material culture of the past in all of its diverse forms. By this time, Judaism and Christianity were well-established and featured prominently in the heterogenous religious landscape. The rare work dedicated by Ibn Al-Kalbi in the ninth century C.E. in the early centuries of Islam on pre-Islamic divinities and religious customs has been until the last thirty years the primary point of access to what Islam deemed the days of Jahiliya, or ignorance.[1] Only relatively recently with the efforts of modern archaeologists and historians have we had the opportunity to encounter the great civilizations of Arabian antiquity and to study their sites, texts, and artworks, although it must be observed that many of these have been deliberately destroyed over the past four years by targeted airstrikes in the ongoing war waged by a coalition of countries led by Saudi Arabia, tallying losses whose importance among the great civilizations like Sumer, Akkad, and Egypt was just beginning to be recognized. Nevertheless, this paper uses both Al-Kalbi’s text as well as these more recent scientific studies in its exploration of the unique character of religious observances in Arabia including customs of animal husbandry, sacrifice, diverse aspects of pilgrimage, and the veneration of natural materials through history and on the eve of Islam which constitute the cultural background from which the distinct features of Islam emerged.

[1] See Marmardjji, M. S. “Les dieux du paganism arabe d’après Ibn al-Kalbi,” Revue Biblique (1892-1940) 35.3 (1926): 397-420.

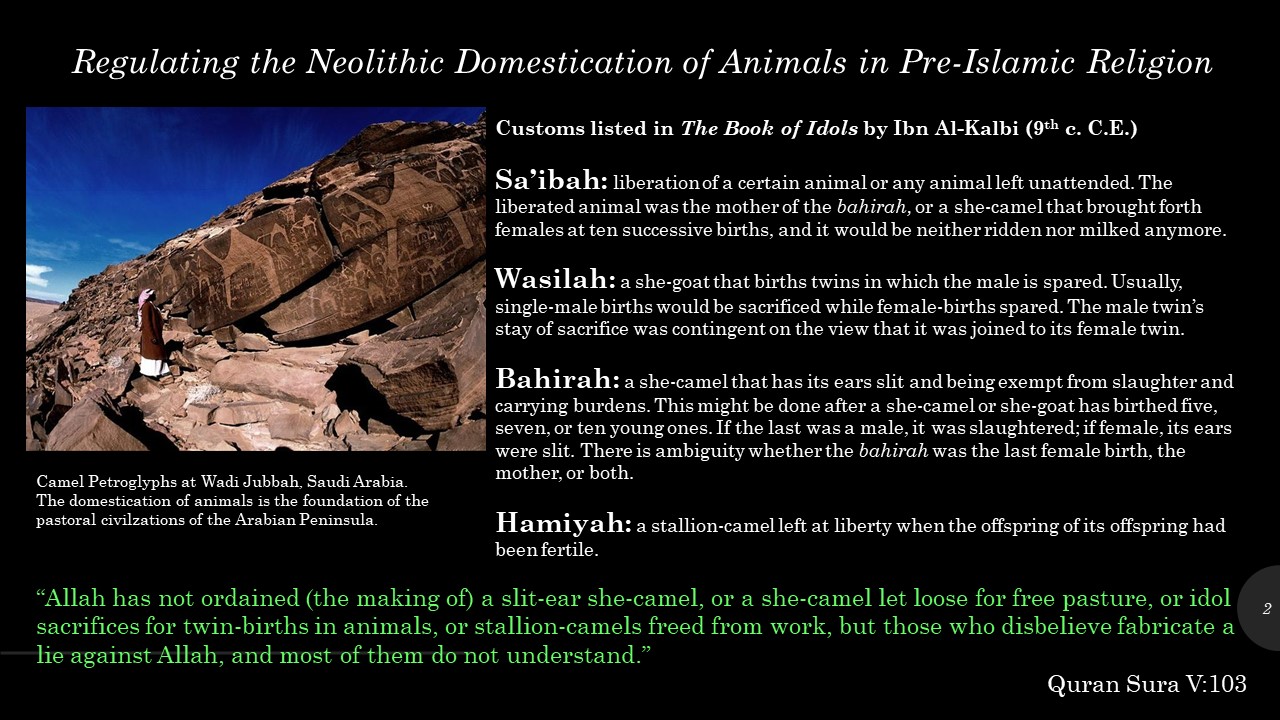

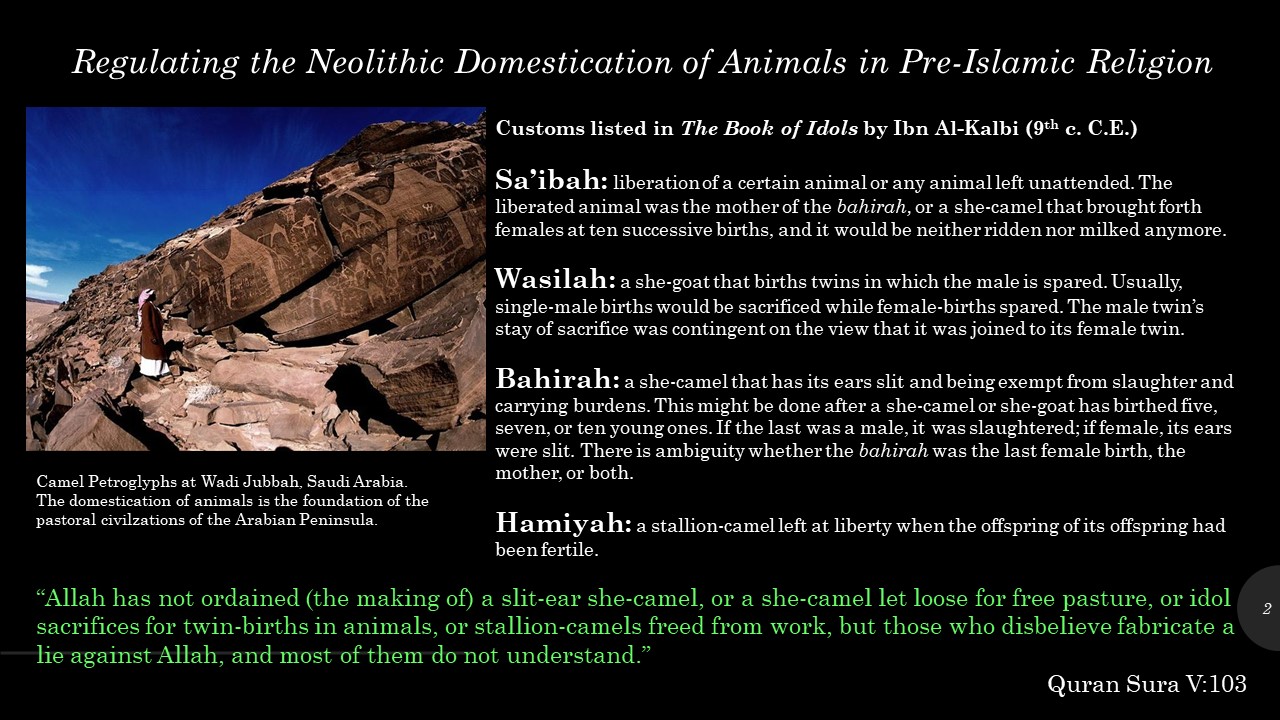

We begin our narrative with the migration of anatomically modern humans out of Africa, across the narrow crossing of the Bab Al-Mandab at the meeting of the Red and Arabian Seas, and into the much wetter and greener Arabia of the Holocene. These early sites of human settlements in the Neolithic are marked by the domestication of animals like camels, goats, and dogs for which the petroglyphs at Wadi Jubbah and other sites from Najran to Petra in Jordan provide ample testimony.[1] A rare historical study of pre-Islamic religion and customs from the early Islamic period, the Book of Idols by Ibn Al-Kalbi written in the early ninth century C.E.,[2] observes that the institution of a series of customs around the sacrifice and management of domesticated animal populations was a diversion from the religion of Abraham and Ishmael which Islam would later prohibit. These are the sa’ibah (the liberation of a certain animal or any animal left unattended; this was often the bahirah- see below), the wasilah (a she-goat that births twins in which the male is spared. Usually, single-male births would be sacrificed while female-births spared; the male twin’s stay of sacrifice was contingent on the view that it was joined to its female twin.), the bahirah (a she-camel that has its ears slit and being exempt from slaughter, carrying burdens, and milking; this might be done after a she-camel or she-goat has birthed five, seven, or ten young ones. If the last was a male, it was slaughtered; if female, its ears were slit. There is ambiguity whether the bahirah was the last female birth, the mother, or both), and the hamiyah (a stallion-camel left at liberty when the offspring of its offspring had been fertile). Only against this cultural context does the full picture of the “new order” of Islam in the Quran’s Sura 5 v. 103 emerge with its dictate that, ““Allah has not ordained (the making of) a slit-ear she-camel, or a she-camel let loose for free pasture, or idol sacrifices for twin-births in animals, or stallion-camels freed from work, but those who disbelieve fabricate a lie against Allah, and most of them do not understand.”

[1] Most recently, see Charloux, Guillaume, Guagnin, Maria, and Norris, Jérome. “Reflection on some rock art traditions of large-sized camels in western Arabia.” Presented at the Seminar for Arabian Studies held in Leiden Friday July 12 2019. Publication forthcoming.

[2] Al-Kalbi, Hisham Ibn. The Book of Idols, Being a Translation from the Arabic of the Kitab Al-Asnam, trans. Nabih Amin Faris. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1952, 6.

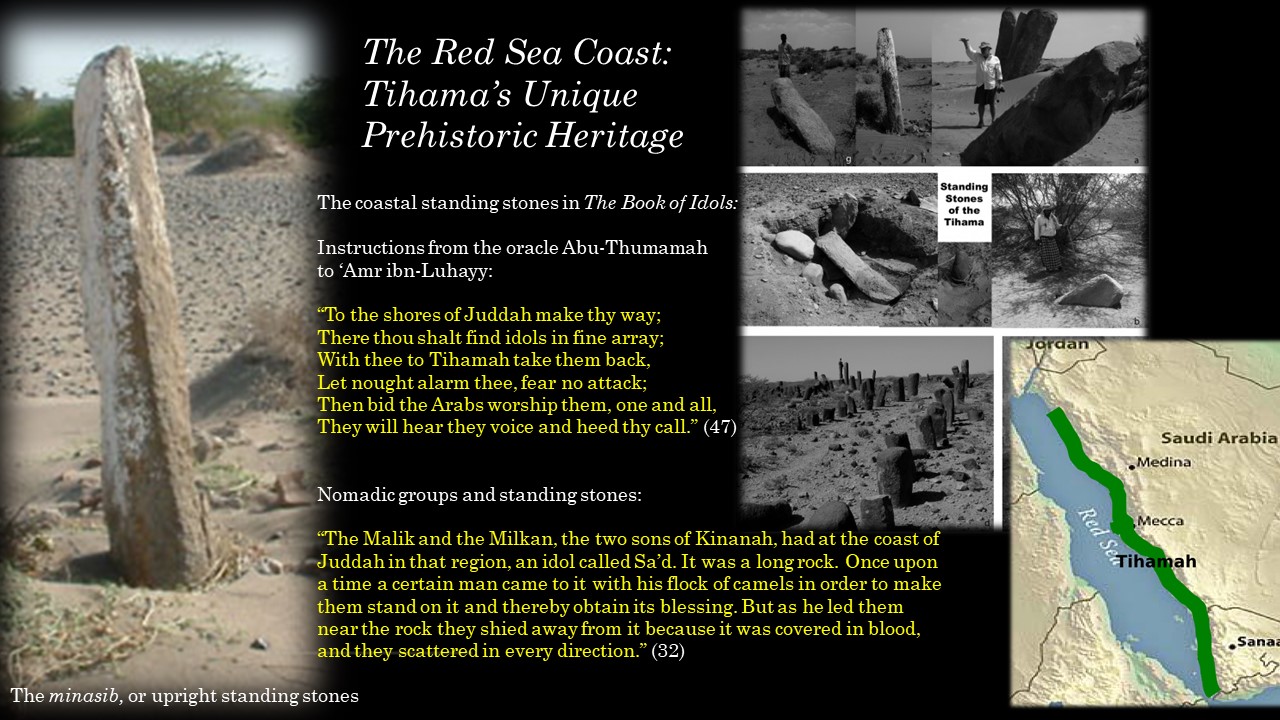

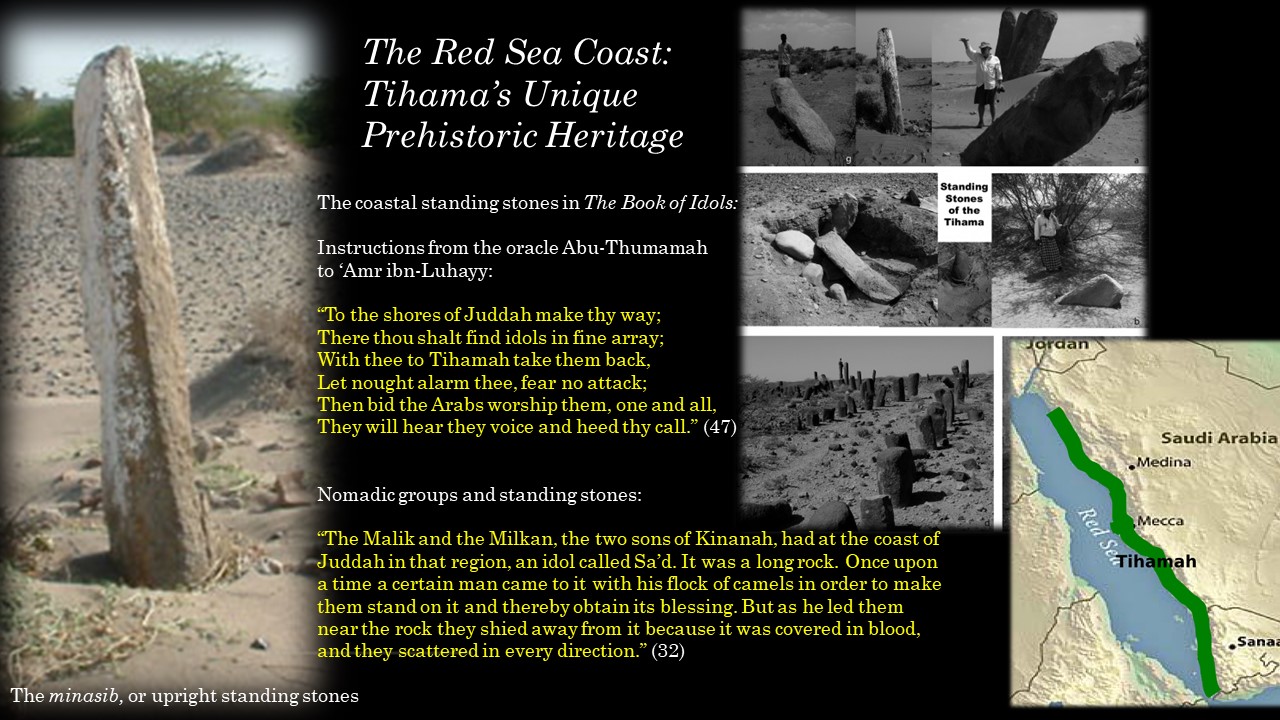

Animals continued to play a central role in the religious and art history of pastoral and agrarian civilizations alike which arose in the coming millennia, but even before this advent, remaining in the prehistoric, we can direct our attention to what would become the literal and spiritual centerpiece of the religious experience through Islam. This is the practice of litholatry or stone worship, evidenced by early arrangements of standing stones on the Tihama plain of coastal Yemen,[1] some of them (as is the case at the site of Al-Muhandid) arranged in circular structures familiar to historians of megalithic architecture at Hagar Qim in Malta, Göbekli Tepe in Anatolia, Stonehenge in England, and many other sites elsewhere. These minasib, or upright stones, possessed a sacred character not only for their original erectors far back in prehistory but also for later periods, when they would be appropriated as stelae or integrated into tombs and religious structures. Writing in the ninth century, there is no expectation that any true memory of the prehistoric erection of these megalithic sites transmitted to Al-Kalbi, yet there is a reference to the transport of several idols from Juddah (perhaps the closer Jiddah on the Red Sea coast of modern Saudi Arabia) to the Tihama, where they were erected and shortly compelled a dedicated pilgrimage. Al-Kalbi relates the instructions of an oracle (a jinn nicknamed Abu-Thumamah) to ‘Amr ibn-Luhayy, whose full significance in the mytho-history of Arabian religion will be explored below:

“To the shores of Juddah make thy way;

There thou shalt find idols in fine array;

With thee to Tihamah take them back,

Let nought alarm thee, fear no attack;

Then bid the Arabs worship them, one and all,

They will hear they voice and heed thy call.”[2]

Another encounter in Al-Kalbi’s with the standing stones of “Juddah,” very likely the same Tihama coast wherein such arrangements and monoliths have been identified by archaeologists in Yemen and Saudi Arabia alike, is the deity Sa’d, described as a “long rock,” which certainly fits the profile of the majority of these prehistoric monuments. The events which led to the abandonment of its worship, which Al-Kalbi recounts in the anecdotal episode of a camel-driver hoping for a blessing believed to be given to animals led to its summit but who becomes enraged by the circumstance of his flock scattered in terror by the blood of earlier sacrifices thereon,[3] reinforce the idea that these sacred sites were locations of pilgrimage and sacrifice for an extremely long duration of time amongst nomadic groups before Islam.

[1] See Khalidi, Lamya, “The late prehistoric standing stones of the Tihâma (Yemen): the domestication of space and the construction of human-landscape identity,” Yémen Territoires et Identités 121-122 (2008): 17-33; “Yemen: Arabia’s Stonehenge,” Current World Archaeology 52 (2012): accessed 8/28/2019. https://www.world-archaeology.com/features/yemen-arabias-stonehenge-3/

[2] Al-Kalbi, 47.

[3] “The Malik and the Milkan, the two sons of Kinanah, had at the coast of Juddah in that region, an idol called Sa’d. It was a long rock. Once upon a time a certain man came to it with his flock of camels in order to make them stand on it and thereby obtain its blessing. But as he led them near the rock they shied away from it because it was covered in blood, and they scattered in every direction. Thereupon the man became furious, and picked up a stone and threw it at the rock saying, ‘Accursed god! Thou hast caused my camels to shy.’ He then went after them until he gathered them, and returned home saying: ‘We came to Sa’d in hope he would unite our ranks, / But he broke them up. We will have none of him. / Is he not but a rock in a barren land, / Deaf to both evil and to good?” Idem, 32. The theme of an animal shying away from the blood of sacrifice is not unique in Al-Kalbi to the story of Sa’d; see also the quotation of Ja’far ibn-abi-Khallas al-Kalbi about the idol Su’ayr of the ‘Anazah: “My young camels were startled by the blood of sacrifice / Offered around Su’ayr whither Yaqdum and Yadhkur go / On pilgrimage, and stand before it in fear and awe, / Motionless and silent, awaiting its oracular voice.” Idem, 35.

Archaeological time and Al-Kalbi’s concept of the past rooted in Biblical events are two entirely different yet not wholly unrelateable time-lines with which the present study must reconcile itself. Al-Kalbi, in a form familiar to Arabian genealogies, establishes the worship of stones in a timeline which goes back to Adam.[1] He relates that the children of Seth (Shith), the son of Adam, initiated the practice of pilgrimage and circumambulation when they visited their primogenitor’s tomb on Mount Nawdh, which the author locates in India. The children of Cain (Qabil), another son of Adam, in response carved their own idol, the first graven image, in order for themselves to have an object of veneration, pilgrimage, and circumambulation. The images were multiplied when, according to Al-Kalbi’s relation, five righteous people died within a month of one another, and the grief-stricken community found solace in five carved statues of their likenesses around which they would circumambulate to pay their respects; these were Wadd, Suwa, Yaghuth, Ya’uq, and Nasr, five antediluvian idols which figure prominently in Al-Kalbi’s volume. He places their creation in the time of Jared (Yarid), the great-great-great-grandson of Adam, and asserts that their worship lasted through the centuries that saw the advent of the prophet Enoch (Idris) and his warning to abandon them through the coming of Noah and the Great Flood, 2,500 years after Adam. This washed the five antediluvian carved idols to Juddah (perhaps Jiddah), where ‘Amr ibn-Luhayy dug them up and subsequently transferred them to the Tihama, as detailed above. Modern archaeology of the past twenty years has brought to light a collection of bronze-age anthropomorphic stelae and statuettes dated to between 3,000 and 1,000 B.C.E., ranging from a female form comparable to the “Venus” prototype of Paleolithic statuettes found in Europe and the Near East, a rare contemporary male counterpart with what has been identified as the glans of the male phallus carved into its lower extremity, a seated group colloquially named “the Forefathers,” and three anthropomorphic stelae from the area around Tayma’ and Ha’il in contemporary Saudi Arabia recently included in the “Roads of Arabia” exhibition of 2011.[2] It is appealing to speculate that these antediluvian proto-idols of Al-Kalbi’s straightforward Adamic timeline may be a response of some kind to the appearance of unearthed prehistoric statuettes in his own time and that of his predecessors.

[1] Idem, 43-6.

[2] Franke, Ute, “Early Stelae in Stone” in Roads of Arabia: The Archaeological Treasures of Saudi Arabia, eds. Ute Franke et al. (Berlin: Wasmuth, 2011), 68-71.

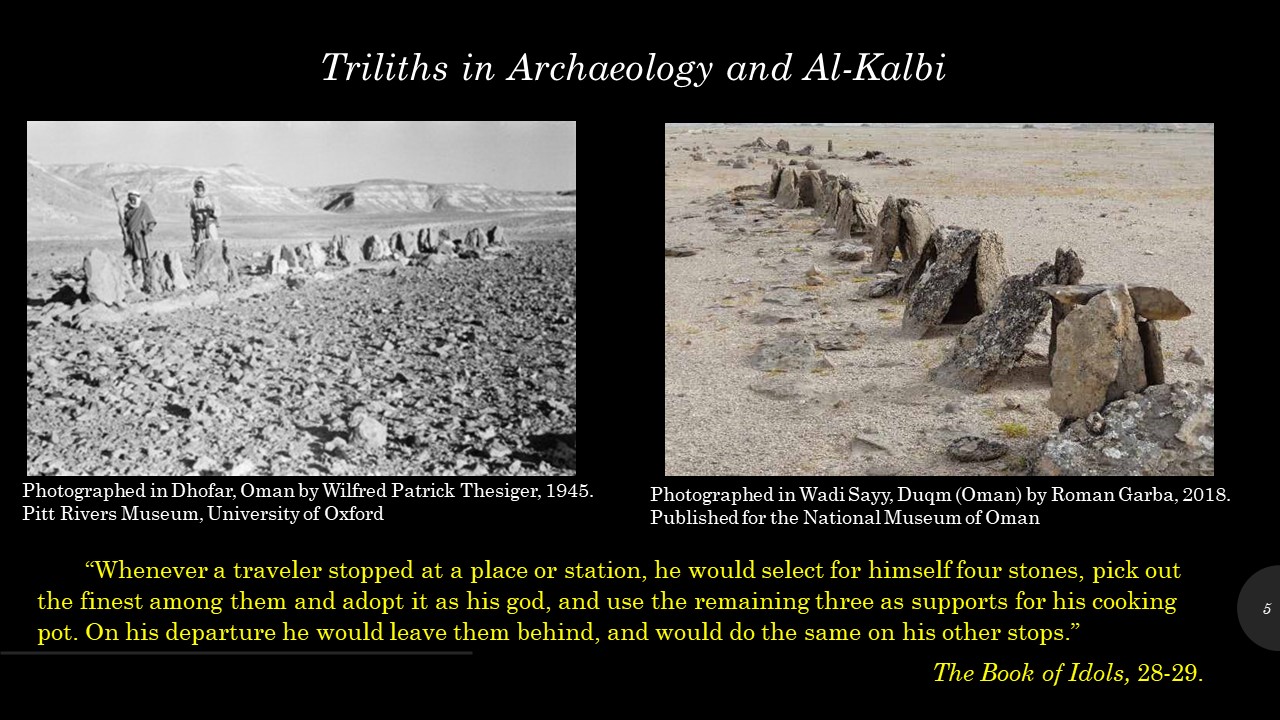

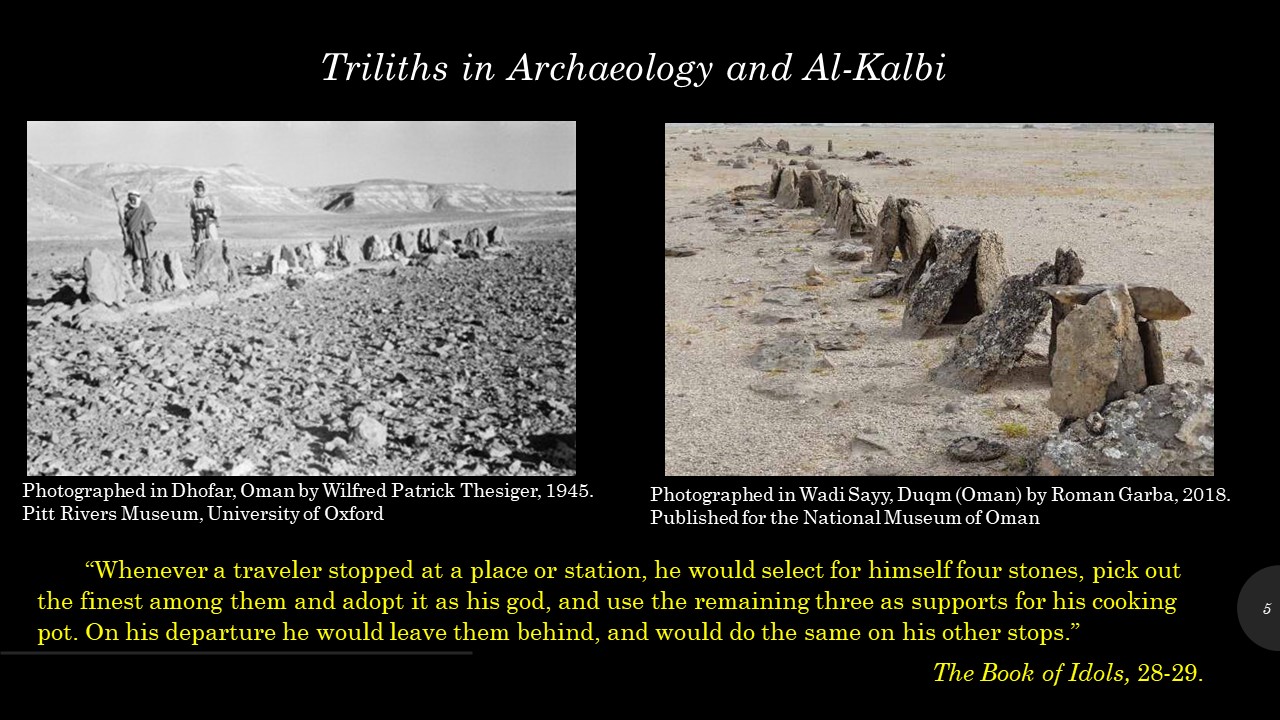

Al-Kalbi categorizes carved stone statues and images as wathan or awthan rather than the term idol, or sanam or asnam, reserved for statues made of wood, gold, silver, or other materials.[1] However, if we take Al-Kalbi at his word, any stone the wandering nomad might come across could and would be adapted to a ritual purpose; these he called ansab.[2] One passage has immediate relevance, so far unconnected in any publication to date, to contemporary archaeologists who study triliths, or three-stone arrangements from the Bronze Age forwards which dot the Arabian Peninsula:[3] “Whenever a traveler stopped at a place or station, he would select for himself four stones, pick out the finest among them and adopt it as his god, and use the remaining three as supports for his cooking pot. On his departure he would leave them behind, and would do the same on his other stops.”[4] This lacuna in historical and archaeological scholarship notwithstanding, the transfer of a trilith arrangement some 600 kilometers’ distance from Duqm to the National Museum Oman in Muscat in 2018 underscores the interest and resources presently dedicated to understanding these prehistoric lithic monuments.[5]

[1] Al-Kalbi, 46.

[2]Idem, 28.

[3] See Giraud, Jessica et al. “The first three campaigns (2007-2009) of the survey at Adam (Sultanate of Oman) (poster),” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 40 (2010): 175-183; Newton, Lynne S. and Zarins, Juris, “Preliminary results of the Dhofar Archaeological Survey,” in ibid.: 247-265; Garba, Roman, “Triliths, the Stone Monuments of Southern Arabia: Assessment in landscape and social context,”Public Lecture at the National Museum Oman. Muscat, Oman. 25 Feb. 2019; Garba, Roman et al. “Trilith monuments of Southern Arabia: preliminary results of excavation seasons 2018 – 2019 and implications on triliths chronology,” Proceedings of the Seminar of Arabian Studies 50 (2020), forthcoming.

[4] Al-Kalbi, 28-29.

[5] “Relocation of trilith monument from Duqm to The National Museum in Muscat, Sultanate of Oman.” Czech Archaeology News, 5 Feb. 2019. Accessed 31 Aug. 2019. https://czech-archaeology-news.estranky.cz/articles/czech-archaeology-news-2019/relocation-of-trilith-monument-from-duqm-to-the-national-museum-in-muscat–sultanate-of-oman..html

Another class of stone idol which features in Al-Kalbi’s medieval account of pre-Islamic worship as well as recent anthropological essays is the stone which is the divinely-transformed human or animal; however, as we shall shortly see, there is an appreciably spectrum to the motives and context for such a transformation to occur, although the worship of this stone by later descendants is common to all. Al-Kalbi informs us of the two stones of Isaf and Na’ilah,[1] two lovers from Yemen whose transgression in the sacred space of the pre-Islamic Ka’bah of Mecca brought down the deity’s petrifying wrath. Al-Kalbi explains their inclusion and changing arrangement among the idols of the Ka’ba of Mecca until the time of Mohamed as well as reveals that menstruating women were not allowed close to Isaf (whether this was also the case with the female Na’ilah is nowhere made as clear.)[2] The Hebrew parallel of Lot’s wife’s transformation into a pillar of salt comes to mind as a relatable phenomenon in broader Semitic mythologies (Genesis 19:26), but examples from Arabian contexts much closer at hand are also to be found. A living relic of this belief and veneration of a transformed rock continues at the pre-Islamic- or rather, trans-Islamic since it draws pilgrimages in the month of Sha’ban each year still- sanctuary of Qabr Hud in an otherwise uninhabited, ravine of the Wadi Hadhramawt in the southern Arabian Peninsula in modern-day Yemen.[3] The antediluvian prophet Hud, whose legend unfolds during the time of the giant ‘Adanites and whose continued worship is due to his prominence in the Qu’ran, given second place in importance only to the Prophet Mohamed, escaped the hostile tribesmen who rejected his preaching with divine aid that opened up a cleft in the rock into which he disappeared (and remains a focal point of the shrine, framed by an opening in the plastered architecture of its interior) to live out his days, nourished only by the milk of his faithful she-camel. At his death, God pitied the camel and transformed her into the giant rock which gives its adjoined terrace, built in the pre-Islamic era but rebuilt as late as the end of the nineteenth century,[4] the name al-Naqa. Another instance of a petrified camel has been noted at the shrine of Mawla Matar, in the Hadhramawt on the old camel track between Mukalla and Wadi Do’an, which preserves the old form of its name “Lord of the Rain” rather than that of any Islamic wali or saint; this rock is smaller than its counterpart at the Qabr Hud, but both sites remain the destinations of yearly pilgrimages and ritual which have preserved distinctly pre-Islamic features explored in detail by Werner Daum.[5]

[1] For their transformed forms, Al-Kalbi uses the term miskhs, which the translator includes in its transliteration without further comment. This term does not appear elsewhere in the translation of Faris, and the full sense in relationship to the body of stone-specific terminology is no further explored. See Al-Kalbi, 8.

[2] “On being transformed into petrified form, they were placed by the Ka’bah in order that people might see them and be warned. Finally, as their origin became remote and, therefore, forgotten, and idol worship came into vogue, they were worshipped with the other idols. One of them stood close to the Ka’bah while the other was placed by Zamzam. Later the Quraysh moved the one which stood close to the Ka’bah to the side of the other by Zamzam where they sacrificed to both.” Idem, 24-25.

[3] See the most recent study of the site and its customs: Daum, Werner. “Qabr Hud revisited: The pre-Islamic religion of Hadramawt, Yemen, and Mecca” in Pre-Islamic South Arabia and its Neighbors: New Developments of Research, eds. Mounir Arbach and Jérémie Schiettecatte (Oxford: British Foundation for the Study of Arabia, 2015), 49-72.

[4] Idem, 51.

[5] Idem, 64. The stark coordinates of the site (14°46’N, 48°48’E) in no way communicate the same evocative picture as the words of Freya Stark reproduced by Daum: “Our track wound between the two [Kawr Sayban, Hadhramawt’s highest elevation and Jabal Matar], and skirted small funnel holes that mark the heads of Wadis Thwinne and Haram, by twisted samr trees, few and bent, until we came to where, like the gates of an Egyptian temple, the two cliff faces stand. Here we entered, with primitive feelings of awe, into the highest defile of the land… and here the Bedouin, responding to the natural religion of the place, have built the shrine and grave of their ancestor, Sheikh Amtar…” 64-65.

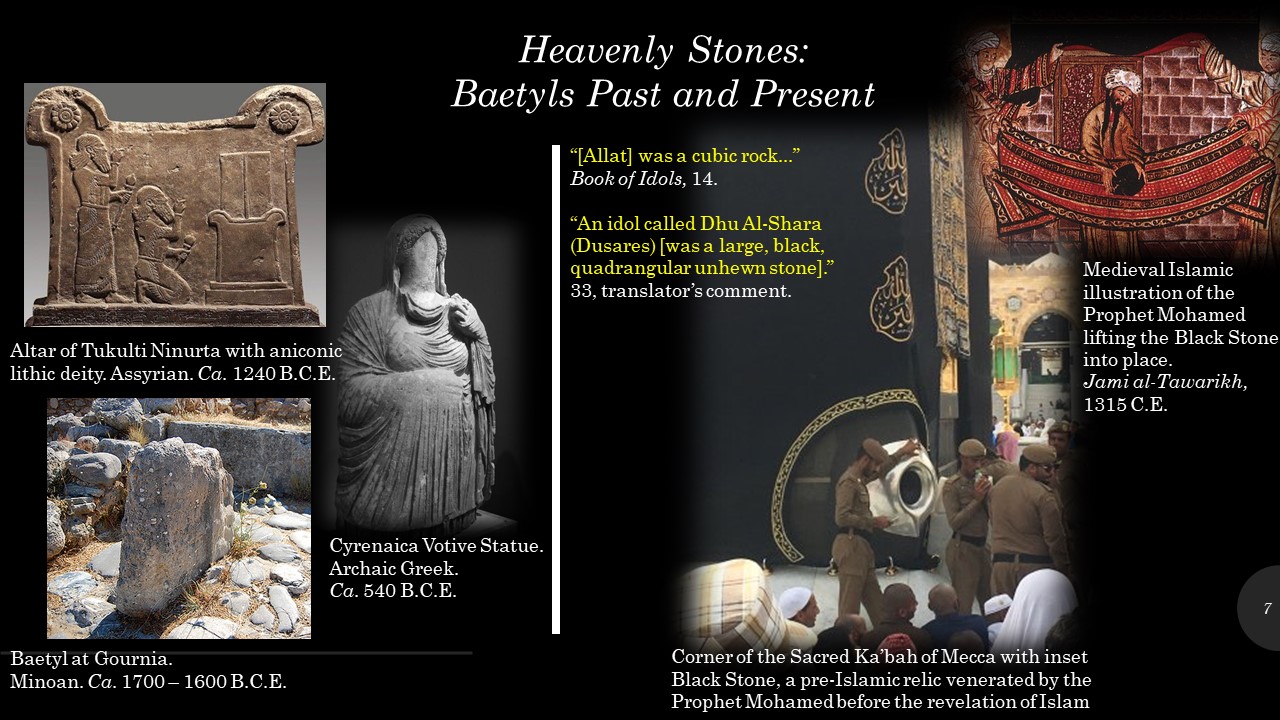

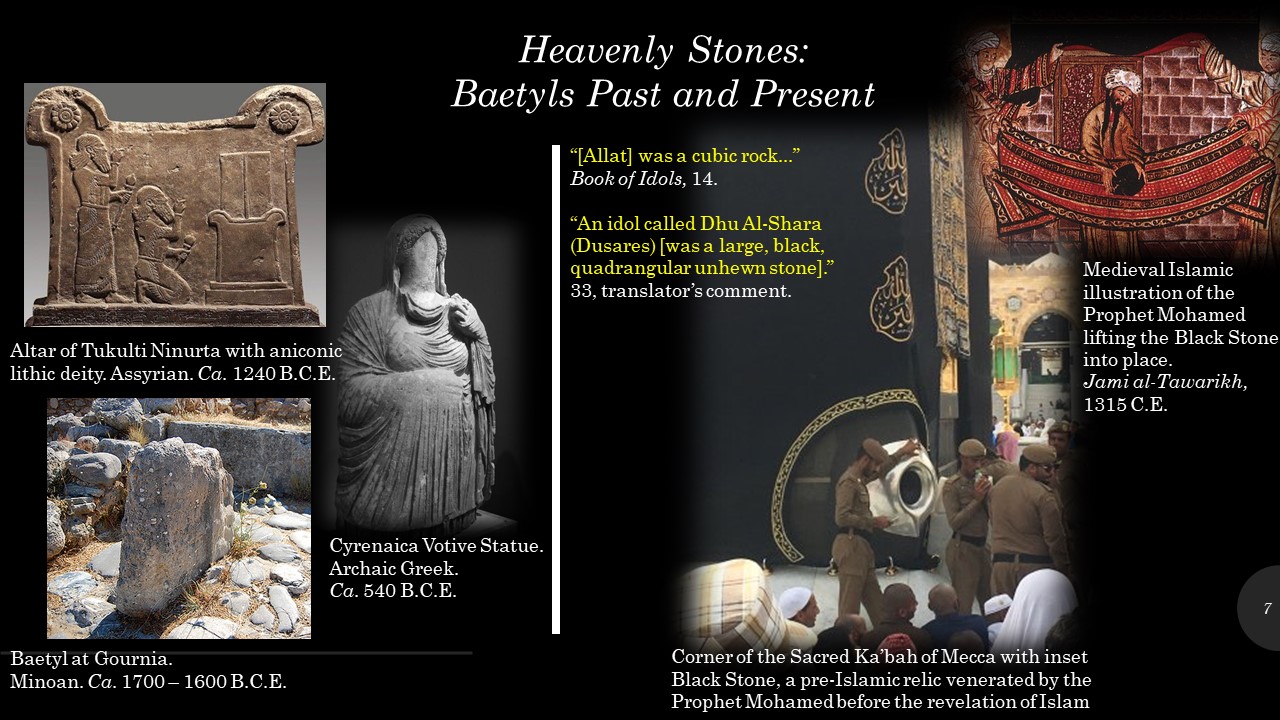

In summary, Al-Kalbi many kinds of stones worshipped by various groups on the Arabian Peninsula before and through the advent of Islam: prehistoric monuments whose obscure origins proved no impediment to ongoing sacrifice and ritual circumambulation, stones upon whose surfaces anthropomorphic images had been carved, stones recognized as miraculous transformations of once-living beings, and any stone elected for the privileged role of temporary baetyl by nomads who organized others nearby into the characteristic triliths that dot the borders of the Empty Quarter. Al-Kalbi’s translator’s use of the term baetyl belies a far-reaching interpretation of litholatry spanning the ancient world and which remains at the heart of Islam. The Greek origins of this term are theorized to be a corruption of the Hebrew Beth-El or “House of God,” the locus of Joseph’s divine dream in the Old Testament (Genesis 28:10-22[1]), but the Arabic bayt however is certainly closer in pronunciation. In any linguistic case, the divine quality to these stones is attached to their origin in heaven abode, the home of God and a host of gods alike across virtually every ancient civilization. It has been argued on a general anthropological level that perhaps the oldest “cult images” probably did not begin as images at all but evolved from meteoric rock and iron fallen from the sky; baetyls, baitulia, or lithoi empsychoi were these kinds of stones which in their earliest incarnations were left in their natural state or minimally carved. Assyrian reliefs document this convention, and archaeologists have identified a likely baetyl as the focus of worship in the ruins of Gournia on Crete by its Minoan inhabitants a full thousand years before Archaic Greek sculpture would appear. The Cyrenaica Votive Statue then from the sixth century B.C.E. is a rare transitional piece which intentionally left the face a smooth, uncarved surface stet in the emerging form of the Archaic kore. Returning to Arabia, we find mention in Al-Kalbi of an uncarved, cubic baetyl as the embodiment of goddess Allat, perhaps better known as a trinity with the other goddesses Manah and Al-‘Uzza, the three “Numidian cranes” or “daughters of Allah” in a scrubbed Quranic passaged dubbed the “Satanic Verses” (Sura An-Najim [53]: 18-22) in the modern period but which Al-Kalbi unflinchingly quotes.[2] Al-Kalbi’s description of Allat’s form also associates it with a “certain Jew” who used to prepare his barley porridge (sawiq) beside it, but this any further clarification to this aspect of its identity and worship would appear hopelessly lost to time.[3] At the time of his writing in the ninth century C.E., Al-Kalbi located the former placement of the Allat baetyl in the place of the left-hand side minaret of the mosque of Taif; while there are a profusion of mosque-sites in the present-day city of Saudi Arabia, an architectural history has yet to be conducted which would establish which mosque to which Al-Kalbi could have been referring. It is worth noting however the linguistic position which the goddess Allat occupies in relation to the name of Allah; the horizontal line which would render the final taa to the feminine taa marbuta, and which is conspicuously absent in the male form of the divinity’s name, is the natural written form of the pre-Islamic female goddess. Another large, quadrangular, and unhewn stone is identified by Al-Kalbi’s translator with the figure of Dhu Al-Shara (or Dusares), chief god of the Nabataeans that had its own splendid dedicated temple at Petra in Jordan.[4] Finally, no discussion of the significance of sacred stones in the Arabian context would be complete without mention of the pre-Islamic Black Stone (hijr as-swad), a much-debated possible meteorite,[5] set into the eastern corner of the Ka’bah in Mecca. Its origin is cast to the beginning of human existence, when it fell from heaven and indicated to Adam and Eve where the first altar should be built; after becoming lost, it was rediscovered by Ishmael, who used it as the foundation stone for the new Ka’bah his father Abraham ordered built. Muslim pilgrims kiss and touch the stone in emulation of the Prophet Mohamed’s treatment of the same before the revelation of Islam, but Islamic scholars underline that it is not the stone being worshipped. This fine point notwithstanding, a salient feature of religion before Islam was the plurality of sacred stones worshipped and the many sites of pilgrimage and circumambulation of said stones, versus the reduction of acceptability and ritual (if not exactly sacrality) to one stone, housed in the Ka’bah of Mecca, and one major pilgrimage with its ritual circumambulation, the Haj required of all practicing Muslims.

[1] And in particular Gen. 28:18 (NIV): Early the next morning Jacob took the stone he had placed under his head and set it up as a pillar and poured oil on top of it.

[2] “By Allat and al-‘Uzza, / And Manah, the third idol besides. / Verily they are the most exalted females (lit. Numidian cranes) / Whose intercession is to be sought.” Idem, 17. On the modern controversy which provoked the 1989 fatwa against the Iranian author Salman Al-Rushdie, see Slaughter, M. M. “The Salman Rushdie Affair: Apostasy, Honor, and Freedom of Speech,” Virginia Law Review 79.1 (1993): 153-204.

[3] Al-Kalbi, 14.

[4] Idem, 33.

[5] Thomsen, E. “New Light on the Origin of the Holy Black Stone of the Ka’ba, “Meteoritics 15.1 (1980): 87.

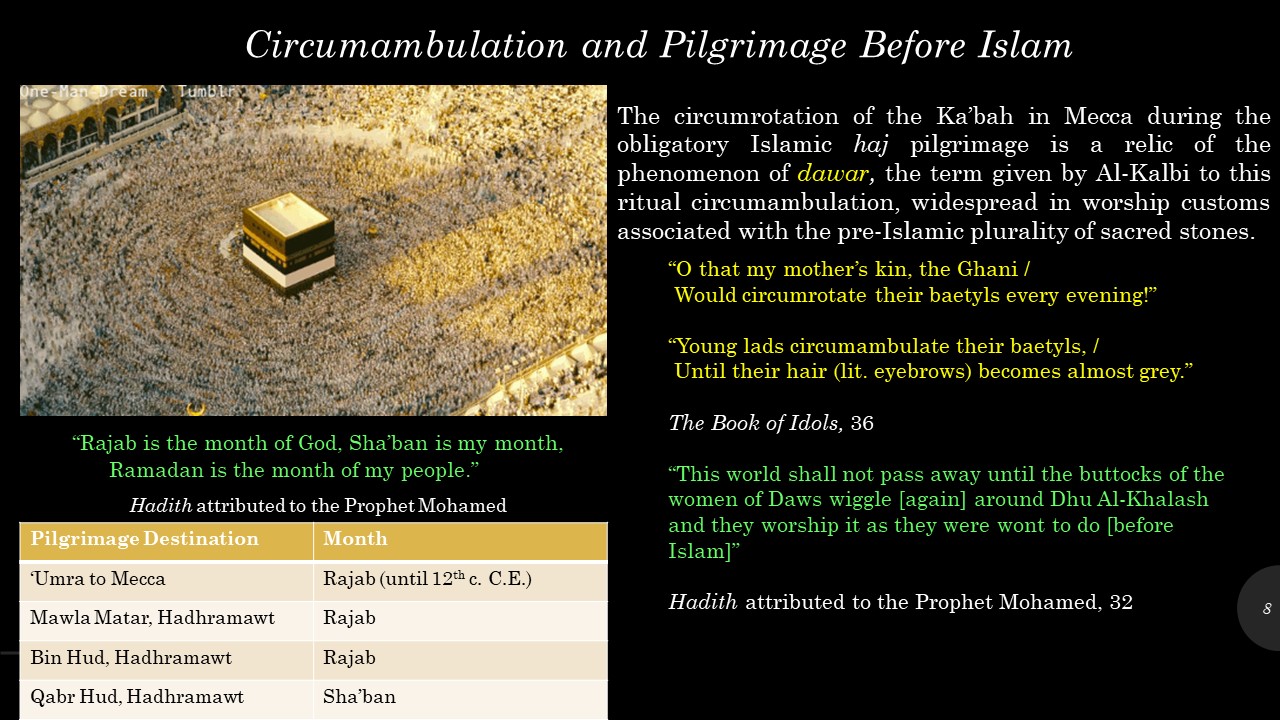

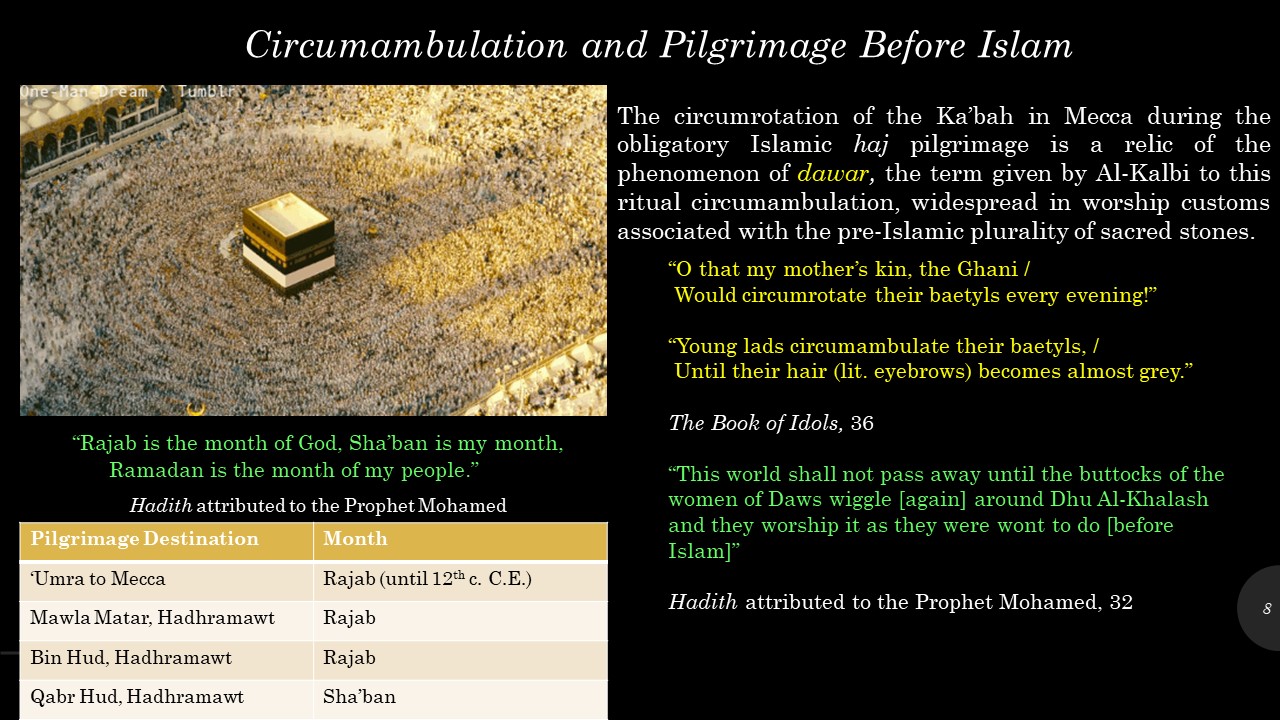

The ritual circumambulation, also encountered described as circumrotation or quite simply the circuit walked around an object of worship is named dawar by Al-Kalbi and testified to in as variety of forms as the worship of various stones.[1] Among the verses related to this phenomenon are included the love-struck ones of ‘Amir ibn-al-Tufayl (“O that my mother’s kin, the Ghani / Would circumrotate their baetyls every evening!”), an excerpt from the ode of al-Muthaqqib al-‘Abdi (“Young lads circumambulate their baetyls, / Until their hair (lit. eyebrows) becomes almost grey.”), and an Islamic prophecy from a hadith, or saying attributed to the Prophet Mohamed (“This world shall not pass away until the buttocks of the women of Daws wiggle [again] around Dhu Al-Khalash and they worship it as they were wont to do [before Islam]”).[2] The act of circumambulating the Ka’bah of Mecca is a continuous practice reduced to a single site in the Islamic Period from a multitude of sacred objects in the age prior, and the Islamic requirement of at least one pilgrimage to Mecca in the lifetime of a Muslim has codified and expanded what was previously a phenomenon of diverse tribes to their diverse respective pilgrimage destinations. The timing of these ritual pilgrimages, reduced to the one principal haj of Islam, also was subject to a break with its past, but not one so dramatic as to render its former practice totally alien. Another hadith attributed to the Prophet of Islam makes direct reference to this revolution the sacred calendar of Arabia underwent in the seventh century: “Rajab is the month of God, Sha’ban is my month, Ramadan is the month of my people.”[3] Daum observed that the pilgrimage to Qabr Hud in the Hadramawt, a site which has maintained a continuous use from the pre-Islamic era, occurs in mid-Sha’ban, while smaller sites like Mawla Matar- mentioned above in conjunction with the rock of a petrified she-camel- and Bin Hud in the Hadramawt take place in mid-Rajab; the “minor haj,” the ‘umra to Mecca, was a phenomenon of the month of Rajab until the twelfth century C.E.[4]

[1] Al-Kalbi, 28.

[2] Idem, 32, 36.

[3] A more detailed discussion can be found in Daum’s study cited above, particularly his conclusion: “In Yemen, those Walis and sanctuaries that go back to the pre-Islamic period have their great annual celebration in either mid-Rajab or mid-Sha’ban. The two months are interchangeable. Islam has abolished their holy nature, and instituted Ramadan instead, but the Yemenis preferred not to take notice of this,” Daum, 66.

[4] Ibid.

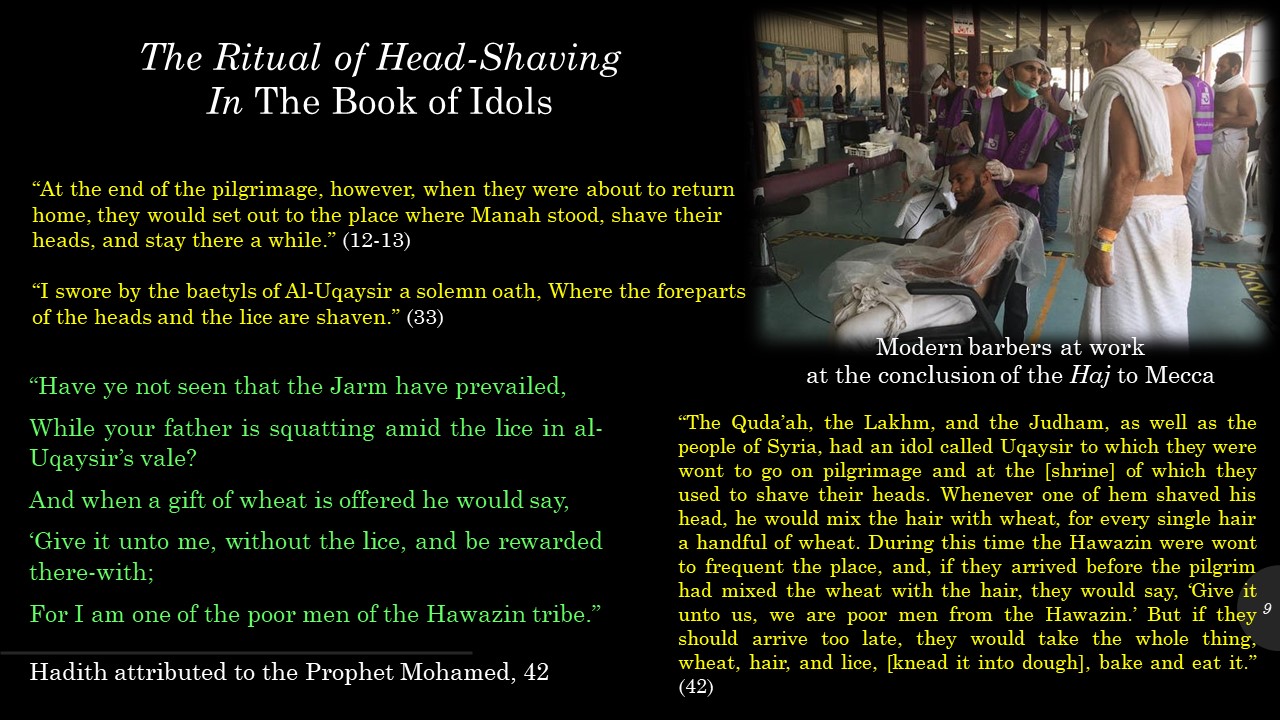

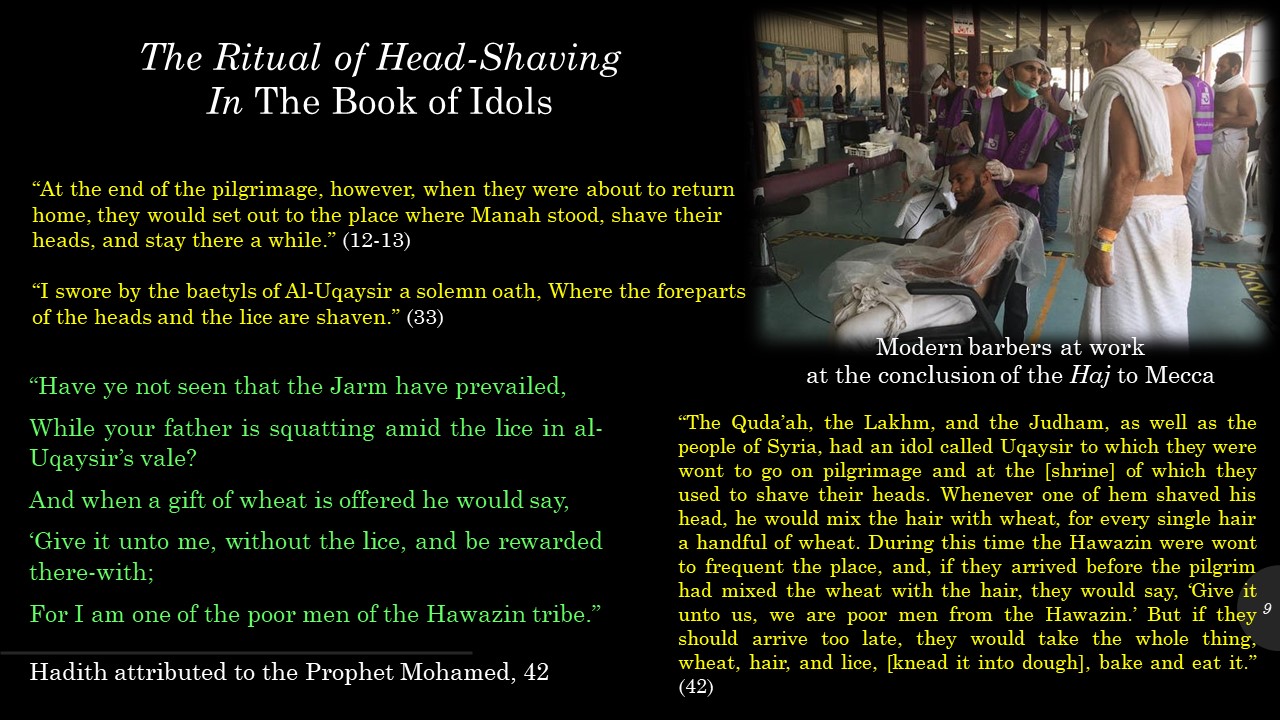

Another feature which has translated to the Islamic haj of the present day amply-attested in the volume of Al-Kalbi is the practice of shaving the head at the conclusion of a pilgrimage.[1] The worship of Manah, another of the three goddesses worshipped around Mecca[2] before Islam of whom Allat was introduced above, closed what appears to have been a long circuit of pilgrimage made by the Quraysh, the Aws, the Khazraj, and the inhabitants of Medina: “At the end of the pilgrimage, however, when they were about to return home, they would set out to the place where Manah stood, shave their heads, and stay there a while.”[3] Another pre-Islamic pilgrimage site which Al-Kalbi locates in the Syrian hills is associated with this act of ritual hygiene: “I swore by the baetyls of Al-Uqaysir a solemn oath, Where the foreparts of the heads and the lice are shaven.”[4] In the case of this latter Syrian idol, the addition of the shaved hair and even lice with wheat offered to the god which would be claimed by a nomadic tribe as the dough with which they would bake bread.[5] This practice is cited explicitly in a hadith of the Prophet Mohamed quoted by Al-Kalb, here excerpted from a longer passage:

“Have ye not seen that the Jarm have prevailed,

While your father is squatting amid the lice in al-Uqaysir’s vale?

And when a gift of wheat is offered he would say,

‘Give it unto me, without the lice, and be rewarded there-with;

For I am one of the poor men of the Hawazin tribe.’”[6]

The clearly-stated preference for the wheat without the lice and hair rules out any construct that the addition of these materials imparted any kind of sacred quality associated in any way with ritual consumption; rather, the picture that coalesces is one of the contrasts of ancient Arabian society between the agrarian, productive settlements which produced and dedicated the wheat with their hair, the “haves,” and the itinerant, impoverished nomads, the “have-nots” for our purposes. By the time of Al-Kalbi, the participation of entire populations, both agrarian communities as well as the pastoral nomads, was a given in Arabian society and religious life; we may start the proverbial clock of the rise of these settled cities of the ancient Arabian Peninsula at 4,800 B.C.E., with the oldest dating of evidence of cultivated sorghum excavated in Oman,[7] signaling a long history of trade and influence between the earliest civilizations of Mesopotamia. By the time of the first mention of the expedition of a gift (namurtu) of semi-precious stones and aromatics from the Sabaean king Karib’il Watar to the Assyrian king Sennacherib ca. 683 B.C.E.,[8] we observe the material development of Sabaean and other South Arabian architecture and religious custom already to a parallel advanced degree of development that has occurred outside the cuneiform historic record. These gaps are only beginning to be filled by the work of archaeologists, epigraphers, and historians working from the South Arabian sources themselves.

[1] For the modern practice and transition from blades to electric shavers, see Naar, Ismaeel. “Barbers of Mecca and why pilgrims shave their head as Hajj nears its end.” Al-Arabiya. 21. Aug. 2018. Accessed 2 Sep. 2019. https://english.alarabiya.net/en/features/2017/09/01/Barbers-of-Mecca-and-why-pilgrims-shave-their-head-as-Hajj-concludes.html

[2] On the location, Al-Kalbi wrote that the idol of Manah was erected on the seashore in the vicinity of al-Mushallal in Qudayd, between Medina and Mecca. For her position in this feminine trinity, see the explicit assertion: “This Manah is that which God mentioned when He said, ‘And Manah, the third idol besides.’ [Sura LIII:20]” Al-Kalbi, 12-13.

[3] Ibid.

[4] This site was frequented by the Quda’ah, the Lakhm, the Judham, the Amilah, and the Ghatafan; the quote is attributed to Zuhayr ibn-abi-Sulma. Idem, 33.

[5] “The Quda’ah, the Lakhm, and the Judham, as well as the people of Syria, had an idol called Uqaysir to which they were wont to go on pilgrimage and at the [shrine] of which they used to shave their heads. Whenever one of hem shaved his head, he would mix the hair with wheat, for every single hair a handful of wheat. During this time the Hawazin were wont to frequent the place, and, if they arrived before the pilgrim had mixed the wheat with the hair, they would say, ‘Give it unto us, we are poor men from the Hawazin.’ But if they should arrive too late, they would take the whole thing, wheat, hair, and lice, [knead it into dough], bake and eat it.” Idem, 42.

[6] Idem, 42-43.

[7] Franke, Ute. “Between Euphrates and Indus: The Arabian Peninsula from 3500-1700 BC,” in in Roads of Arabia: The Archaeological Treasures of Saudi Arabia, eds. Ute Franke et al. (Berlin: Wasmuth, 2011): 73-85, 73.

[8] Sumerian and Akkadian written sources’ geography has been reconciled to modern maps to a limited extent: the Persian Gulf as an Upper and Lower Sea, Oman as copper-rich Magan, Tarout Island in Saudi Arabia as Dilmun. Idem, 81.

Offerings were a central aspect of worship in pre-Islamic Arabia, and the rendition of a certain percentage or tithe from the variety of crops’ yields was commonplace. This perhaps is the critical socio-economic context from which the votive iconography of the Qatabanian Dhat Himyam type- with the left hand holding stalks of wheat close to her chest while the right is raised in an apparent gesture of blessing or salutation- must be placed (or at the least argued, albeit in a future study).[1] Elsewhere, vestiges of the association of a successful crop of wheat and the promise of a ritual bride given to the deity are made explicit by Werner Daum in the Hadhramawt as well as in the Tihama coastal region,[2] and the link between the fertility of crops and the rituals of hieros gamos, the sacred marriage ceremony, in ancient Saba is in the beginning stages of study.[3] In the context of the ongoing pilgrimage to Qabr Hud in the Hadhramawt, we see a variability about the precise time of the pilgrimage between nomadic and settled agrarian groups; whereas the nomadic bedu maintain the full moon day of the 15th of the month as the most reliable time to undertake their ziyara, we see a postponement of the trip to after the time of the date harvest for the agrarian communities of the inner Hadhramawt.[4] Equally if not more prominent however in pre-Islamic religion than the rendition of crops was the sacrifice of livestock and the subsequent division of its meat among the pilgrim population. The slaughter of animals continues to be a salient feature to the Islamic holidays, the various occasions of Eid celebrated throughout the year, but as we have seen in the matter of pilgrimage-calendars, circumambulation, and the preservation of a baetyl at Mecca, much older practices have been preserved with procedural differences that make them “Islamic” rather than “pagan.” As we saw above in the initial section dedicated to the aspects of animal husbandry abolished by Islam- the sa’ibah, wasilah, bahirah, and hamiyah– a rigorous system had long been in place to determine what was sacrificed at what time and in what way. Before the mandates of Islam, large animals (for ancient Arabians, bulls in the south; camels in the north) were sacrificed as aqira (pl. aqa;ir)[5] with a heavy blow dealt to the head after the tendons were cut, rendering it immobile physically as well as in relation to the wider linguistic context of Arabic (e.g. aqara as immobile propert or real estate in the Western sense). This term is also encountered as ‘atira (pl. ‘ata’ir) are more specifically rajabiya, the sacrifices offered in the months of pre-Islamic sacred month of Rajab (alternatively Sha’ban).[6] Daum cites hadiths ascribed to the Prophet Mohamed which reinforce this break with tradition[7] and the Islamic substitution of a new protocol, which called for the living animal’s throat to be cut. Historic accounts of the now-vanished phenomenon of bull sacrifice at the site of Qabr Hud, proposed to have lasted through the turn of the twentieth century, in Daum’s study plainly articulate[8] what archaeologists have excavated in Sabaean and other South Arabian civilizations’ temple sites in the last thirty years: the public nature of the sacrifice in its own dedicated architectural setting. It is a commonplace of Al-Kalbi’s volume to assert that sacrifices were made before its various idols, and some specifics of location are also given: the sacrificial site to Al-‘Uzza (the third goddess of the divine feminine trinity before Islam) was called al-Ghabghab,[9] and the transformed stones of Isaf and Na’ilah described above were associated with locations of sacrifice by Zamzam in Mecca.[10]

[1] See Pirenne, Jacqueline. “Notes d’archéologie sub-arabe: I. Stèles à la déesse dhat himyam (hamim).” Syria 37 (1960): 326-347. On the dedication to Dhat Himyam of other tokens of fertility, namely votive phalluses, see Frantsouzoff, Serguei A. “The Inscriptions from the Temples of Dhat Himyam at Raybun.” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 25 (1995): 15-28.

[2] An ancient pilgrim’s chant (tahwid) alludes to this practice: “If the halba (a Yemeni variety of wheat) be safe from Taraf (a star that brings a crop-damaging cold spell) for a night / We’ll build a tent, and the Prophet (Hud) shall have a bride.” Daum, 59. On Tihama see Daum. “A pre-Islamic Rite in South Arabia,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 1987: 5-14.

[3] Maraqten, Mohammed. “Sacred spaces in ancient Yemen – The Awam Temple, Ma’rib: A case study,” in Pre-Islamic South Arabia and its Neighbors: New Developments of Research, eds. Mounir Arbach and Jérémie Schiettecatte (Oxford: British Foundation for the Study of Arabia, 2015): 107-133; 111-112; Müller, W. W. “’Heilige Hochzeit’ im antiken Südarabien,” in Studies in Oriental Sulture and History. Festschrift for Walter Dostal, eds. A. Gingrich et al (Frankfurt: Lang, 1993): 15-28.

[4] Led by the Ba Abbad Sheikh as detailed in Daum, 58.

[5] Versus the dhabaha (pl. dhabiha) sacrifices of smaller animals like sheep or goats. Daum, 60.

[6] Idem, 61-62.

[7][7] “Do not eat from an animal that the Arabs have slaughtered as ‘aqira – I have to believe that it was dedicated to a divinity other than Allah” and more to the point, “No ‘aqra in Islam.” Idem, 60.

[8] “And they sacrifice the ‘aqa’ir before [=on the platform surrounding] the qubba, everybody according to his intention and the obligation of his heart, and this is in fulfilment of the vows he had made.” Ibid.

[9] Further locales dedicated to the goddess Al-‘Uzza, along with material finds and a proposed iconography among the Nabataean Arabs are to be found in Patrich, Joseph. “’Al-‘Uzza’ Earrings,” Israel Exploration Journal 34.1 (1984): 39-46. See as well Lindner, Manfred. “Eine al-‘Uzza-Isis-Stele und andere neu aufgefundene Zeugnisse der al-‘Uzza-Verehrung in Petra (Jordanien),” Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins (1953-) 104 (1988): 84-91.

[10] Al-Kalbi, 18-19, 25.

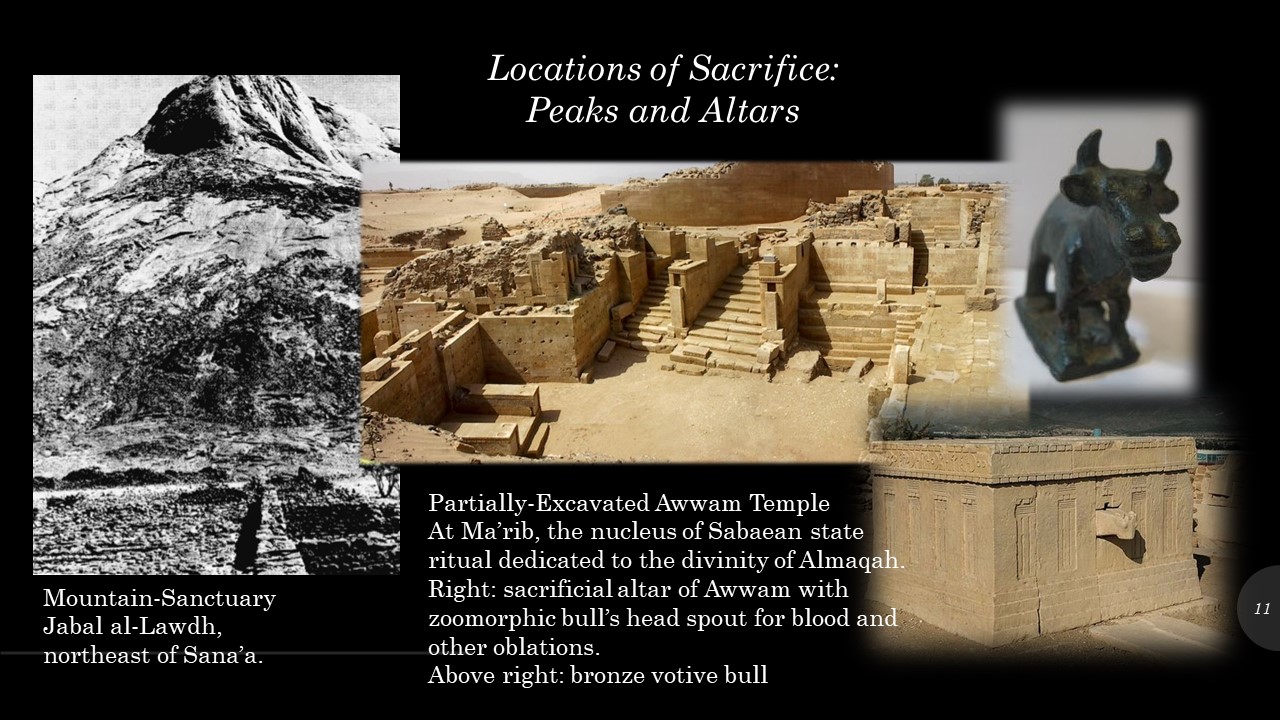

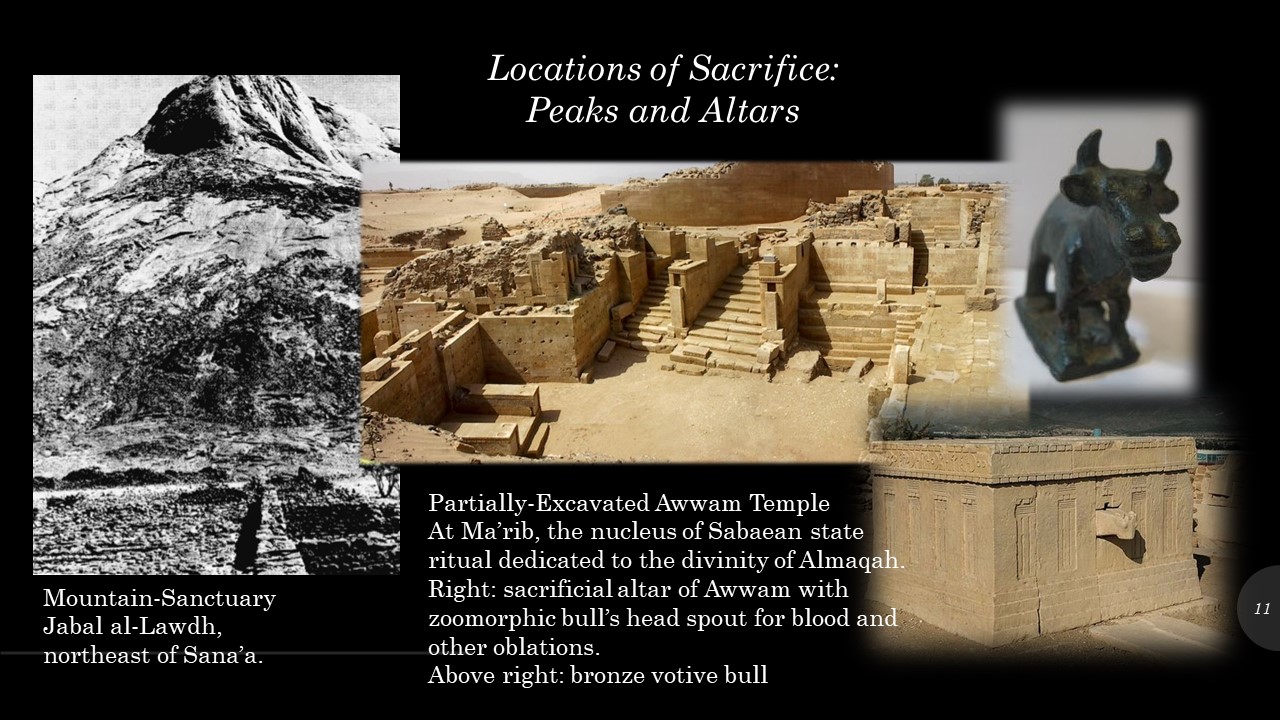

The inseparable role between sacrifice and religious veneration is the critical context which explains the idols of Sa’d, Su’ayr, and those blood-smeared rocks and baetyls encountered in the Arabian wilderness and earlier in this study, and these more rustic practices included sacred mountain peaks as well. An isolated verse in Al-Kalbi, “He moved therefrom and reached a mountain top, / Like a high altar sprinkled with the blood of sacrifice”[1] is our study’s introduction to the phenomenon of Sabaean mountain-temples as doubles of the primordial mount, a “pillar of heaven, and the omphalos or cosmic naval related most recently in a study by Mohammed Maraqten.[2] The well-known sanctuary at Jabal al-Lawdh[3] and lesser-known sites such as Jabal Balaq al-Awsat[4] and Jabal Riyam, the last of which is the only of this group mentioned by Al-Kalbi,[5] are prototypical examples of sacrality which later, more refined architectural temples of the Sabaean and other ancient South Arabian imitated in concept and epithet; the description “’r’wm”, Mount of Awam, is applied to the principal temple of the Sabaean kingdom of Ma’rib, even though it is not constructed on a mountain (rather it functions as the mountain).[6] So too can we draw a parallel between the rustic conventions of sacrifice and the refined lexicon of architecture and ritual furniture which served the same purpose and which has come down to the present in diverse instances of the archaeological record and published studies.[7] The Awwam Temple dedicated to Almaqah- colloquially called the Mahram Bilqis after the Biblical Queen of Sheba in the enduring Yemeni memory[8]– functioned as the epicenter of the Sabaean state religion, and its monumental sacrificial altar echoes in its form the architectural features of the divinity’s “house” (as sacred sites were and continue to be conceived; consider the ongoing usage of the linguistic construct of the Sacred House of Mecca) in which it originally stood. Not only bayt (house; Sabaean: byt) but also mahram (Sabaean: mhrmm) as well as the use of Ka’b for pre-Islamic sites anticipate the common Islamic monikers of the Meccan Ka’ba.[9] This echo or “doubling” of temple architecture on the forms of its sculpted sacrificial altar is also seen at a Sabaean temple dedicated to Almaqah across the Red Sea in Ethiopia, indicating that this was a widespread convention in elite temple sites of the culture and period.[10] The Awwam and Ethio-Sabaean altar alike both also possess a spout in the form of a bull’s head, indicating that a channeled flow of the blood or other fluid offered was considered on some level to be a sacred performance to which the object’s design added a further element of display. The dedicatory statuettes and plaques with bulls’ heads in relief which proliferate in South Arabian archaeology (and in today’s black market of antiquities) are object which further echo or double the phenomenon of rendering animal sacrifice to the god, albeit on the smaller scale of an individual, rather than the communal nature of the living animal’s donation. It is also worth noting that the bull itself (thawr of modern Arabic) was conflated with the divinity of Almaqah, which finds mentions in inscriptions as the thwr b’lm (“the Bull of Ba’lum,” e.g. the Bull of the Lord), ‘lmqh w-thwr b’lm b’ly ‘wm w-hrnm (“Almaqah and the Bull of Ba’lum, the two Lords, of Awam and of [the temple] Harunum”) and which has also been associated by Maraqten with the qualities of a storm god.[11]

[1] “He moved therefrom and reached a mountain top, / Like a high altar sprinkled with the blood of sacrifice.” Idem, 29.

[2] See Maraqten, 117;

[3] Robin, Ch. J. and Breton J.-F. “Le sanctuaire préislamique du Gabal al-Lawd (nord-Yémen),” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres 126.3 (1982): 590-629; Daum, W. “Der heilige Berg Arabiens,” in Im Lande der Königen von Saba: Kunstschätze aus dem antiken Jemen, eds. W. Daum et al (Münich: Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde, 1999): 223-232.

[4] Schmidt, J. “Tempel und Heiligtimer in Südarabien. Zu den materiellen und formalin Strukturen der Sakralkunst,” Nürnberger Blätter zur Archäologie 14 (1997-1998): 10-40.

[5] “The Himyar had also another temple [bayt] in Sana’a. It was called Ri’am; the people venerated it and offered in it sacrifices. According to one report, they used to receive communications from an oracle therein.” Al-Kalbi’s description continues with an account of its destruction in the reign of the Himyar king (Tubba’) converted to Judaism, almost definitely Dhu Nuwas in the early sixth century C.E. Al-Kalbi, 10-11.

[6] Maraqten, 117.

[7] See Dostal, W. “Some remarks on the ritual significance of the bull in pre-Islamic South Arabia” in Festschrift R. B. Serjeant, Arabian and Islamic Studies, eds. R. L. Bidwell and G. R. Smith (London: Longman, 1983): 196-213.

[8] This Biblical personage has become conflated with the prominent queen of pre-Islamic Yemen who lived during the eighth century B.C.E., the daughter of the King Hudhad who saved an enchanted ibex from a wolf that became his bride and Bilqis’s jinni-mother. See Abdulaali, Wafaa. “Echoes of a Legendary Queen: Contemporary women writers revise and recreate Sheba/Bilqīs,” Harvard Divinity Bulletin 40 (2012). Accessed 31 Aug. 2019. https://bulletin.hds.harvard.edu/articles/summerautumn2012/echoes-legendary-queen

[9] Maraqten lists these and further Sabaean terminology attested to in the inscriptions of the Awwam temple. Maraqten, 108-110.

[10] Scnelle, Mike. “Ethio-Sabaean libation altars – First considerations for a reconstruction of form and function,” in Pre-Islamic South Arabia and its Neighbors: New Developments of Research, eds. Mounir Arbach and Jérémie Schiettecatte (Oxford: British Foundation for the Study of Arabia, 2015): 143-151.

[11] Maraqten, 111; I have substituted th for Maraqten’s notation of the syllable as ṯ for greater ease of Western pronunciation as well as for reasons of personal familiarity; the distinguished family in Yemen to whom I owe my great love and fascination for South Arabian subjects bears the name Al-Thor, and very ancient bull-iconologies and themes continue to play a role in their collective identity. These constructs of the Sabaean bull-deity have elsewhere been explored in the context of an expiatory sacrifice for homicide (hajar/tahjir) and the Islamicized thawr al-Id, on the occasion of Eid. See Daum, 62.

The primordial storm god, the bringer of thunder, “thou whose lightning flash flickers forth from the East,”[1] and most dramatically (and importantly) the harbinger of great quantities of water to an otherwise predominantly-arid landscape is a central figure in the worship of ancient Arabia which still bears recognizable traces in aspects of pilgrimage sites and practices through Islam and the present day. The uniform topography of some of the most-frequented pilgrimage sites before Islam has led to the reconstruction by Werner Daum of a detailed analysis of the role of seasonal floods and water sources in the worship-practices of Arabia before (and to an extent through) Islam. Daum’s hypothesis that sites like Qabr Hud and the Ka’bah of Mecca[2] were intentionally built in the course of seasonal flood plains in deep ravines, or sh’ib, around which the roaring waters would predictably and dramatically inundate the area finds a parallel in Al-Kalbi’s description of the temple site of Al-‘Uzza in just such a topography.[3]Certainly, perhaps the most lauded accomplishment of the ancient Sabaean civilization was their advanced grasp of hydraulic engineering for which the Marib Dam stands as an eternal monument, damage from a 2015 Saudi air strike notwithstanding.[4] The form which largely stands today can be dated to between the eighth and sixth centuries B.C.E., but scholars attest to the activity of South Arabians of constructing sophisticated systems of channels- falajs in some context- to harness seasonal floods, groundwater, and other sources for intensive agriculture from a much more distant antiquity still.[5] Above we have seen a chant from the Qabr Hud pilgrimage preserve the memory of making a kind of agreement with the deity for a crop that has weathered the perils of unpredictable weather; the same pilgrims’ hymn about rain gets right to the point, “We made the pilgrimage to you, Bin Hud, and to your wadi, we now want a miracle, we want the water to flow down.”[6] In the Qur’an, the Sura Hud (v. 52) preserves this ancient rain-making association: “[if you, the people of ‘Ad, return to God, so spoke Hud the prophet, then:] will he send down the skies [i.e. the rains] upon you, showering upon you rain in abundance…”[7] Elsewhere the songs sung at Mawla Matar, the shrine which we recall has preserved its old name “Lord of the Rain,” express the same urgent sentiment,

Rain! Oh Lord of the Rain!

Turn, oh turn the floods!

Oh God, water us with the floods

So that every wadi will drink its crop-bringing share

Oh God, water us with rain![8]

On the subject of the divine acts of making rain and releasing floods, modern scholarship has revealed a rich landscape of South Arabian religion whose very purpose and complex ritual apparati it would seem evolved to serve that fundamental end.

[1] This is a loosely paraphrased line from a hymn sung by pilgrims to Qabr Hud on the descent from the shrine; Daum observes that the thunder-god they addressed is the pre-Islamic figure of Hud himself. Idem, 57.

[2] The batn Makka is the deepest spot of the ravine where the Ka’bah was erected. See Daum, 50.

[3] “The Quraysh had dedicated to it, in the valley of the Hurad, a ravine [shi’b] called Suqam and were wont to vie there with the Sacred Territory of the Ka’bah.” Al-Kalbi, 17.

[4] Romey, Kristin. “’Engineering Marvel of Queen of Sheba’s City Damaged in Airstrike,” National Geographic Online. 3 June 2015. Accessed 3 Sep. 2019. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2015/06/150603-Yemen-ancient-Sheba-dam-heritage-destruction-Middle-East-archaeology/

[5] For an introduction see Harrower, Michael J. “Hydrology, Ideology, and the Origins of Irrigation in Ancient Southwest Arabia,” Current Anthropology 49.3 (2008): 497-510.

[6] Daum, 63.

[7] Quoted from idem, 70.

[8][8] Idem, 64.

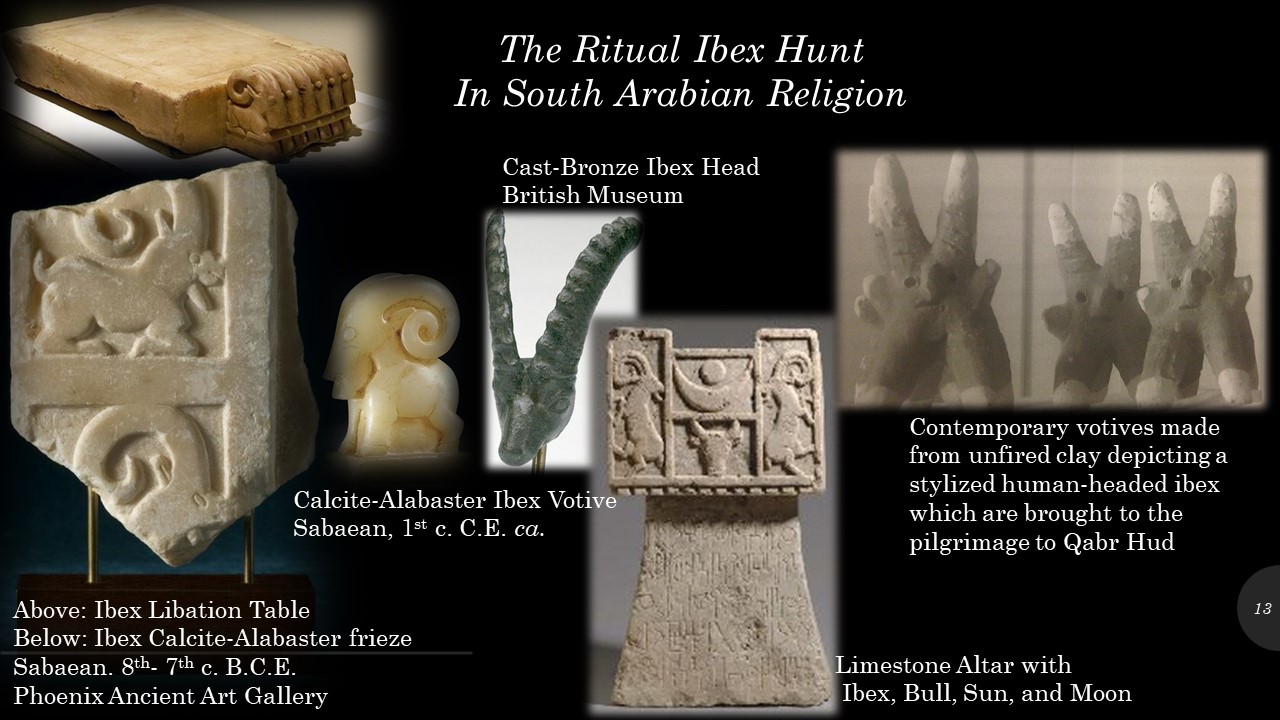

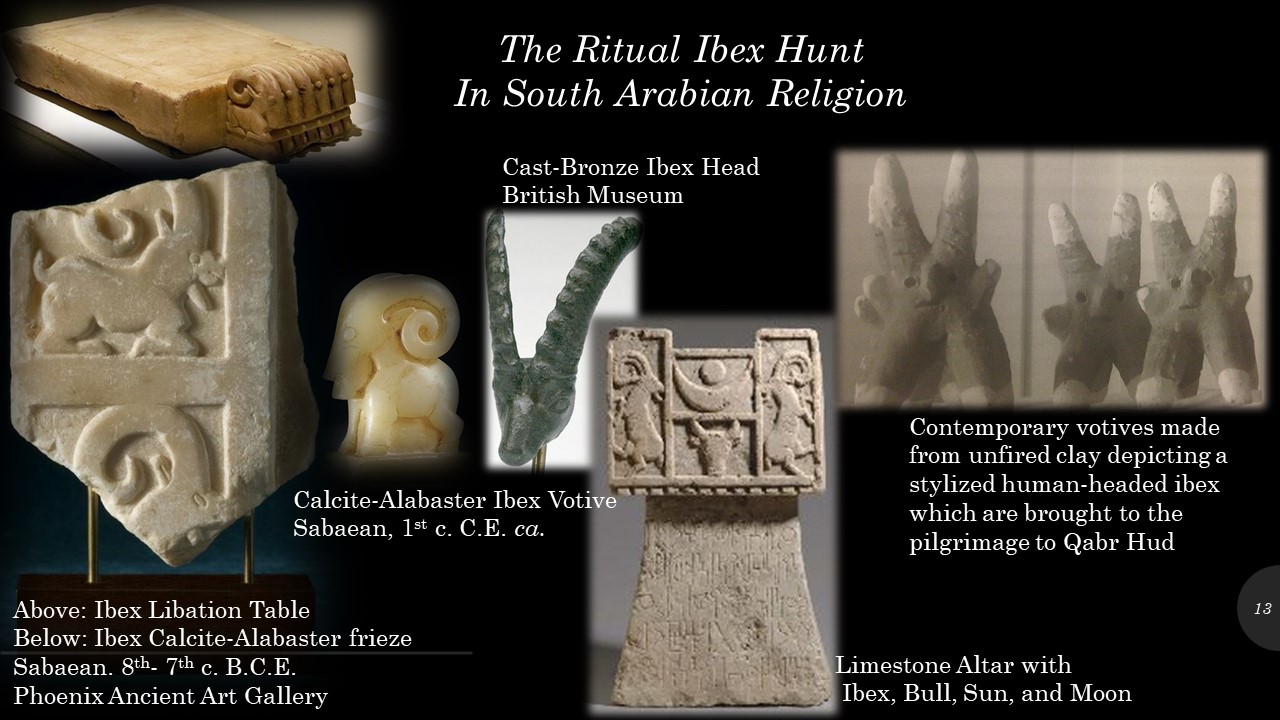

Here, in the reconstructed sacred drama of the rain acted out in pre-Islamic South Arabia, we significantly depart from anything in the vast stretches of the Islamic world, with exceptional vestiges noted by Daum that have persisted in the Hadhramawt valley of south-eastern Yemen. These confirm what has elsewhere been attested to in Sabaic epigraphy and the forms of that nascent field we might begin to delineate as South Arabian art history. Whereas Islam to a certain extent preserved the ritual of the sacrifice of domesticated livestock, replacing rams and lambs conventionally with the large aqira bulls and camels of the northern Arabs, there is no equivalent preservation of the much older tradition of the hunt of the undomesticated animal, principally the wild ibex that are indigenous to the area. Bronze-age petroglyphs in north Yemen testify to the antiquity of the practice, as well as its importance to the prehistoric people who repeatedly carved either the ibex alone or hunt-scenes with multiple figures[1]. Ibexes proliferate in Sabaean art and architecture: as sculptural votives, reliefs on plaques, and integrated as architectural cornices of both temple and altar. In the body of scholarship which has grown around the phenomenon of the survival of this ancient hunt even in contemporary Hadhramawt, in defiance of long-standing disapproval from Islamic authorities,[2] has furnished details which are echoed in the forms ancient South Arabian artwork. The requisite that the ibex hunted be the oldest male with the largest set of horns is clearly identifiable in the stylized ibex iconography in which the spiral curl of the horns in profile is the dominant form of its composition. The sculptural votives in a spectrum of minerals and stone, bronze, clay, and other materials may probably have functioned as figured doubles, much like the figured bulls may be objectified offerings of the sacrificial livestock. Daum identifies and publishes for the first time images of the continued phenomenon of ibex-votives, these made of unfired clay, which are continued to be brought clandestinely on the Qabr Hud pilgrimage.[3] However, the bull iconography which we encountered earlier in this study also functioned as the visual evocative of the god Almaqah for the Sabaeans and host of other divinities in the wider Near East; just so did the ibex also “double” for a specific divinity, albeit one whose precise identity and character remain more obscure. That the ibex hunt is a ritual act is indicated by the state of ritual purity its hunters must enter before its beginning; the triumphant, ritualized announcement at the slaughter, “the old man is killed!”[4] was the necessary prerequisite for what has been identified as a divine marriage banquet to proceed between a bride, Wasila al-sabb (“Wasila, the woman who causes abundant rain and makes the wadi flow”[5]) and the primordial thunderer, Hud at the shrine of the Hadhramawt but this could be Almaqah or the host of names for various sky-gods known to the region in antiquity.

[1] Jung, Michael. “Rock Art of North Yemen,” Rivista degli studi orientali 64 (1990):255-273.

[2] See Daum, 68-69, Rodionov, M.A. “The Ibex Hunt Ceremony in Hadramawt Today,” New Arabian Studies 2: 123-129; Bin ‘Aqil, A. J. Qanis al-wa’l fi-Hadramawt (al-Khubar, 2004).

[3][3] Daum, 67.

[4] Wa-l-shaiba-maqtul; idem, 69.

[5] Daum’s construction, idem, 59. Daum cites as well a Yemeni folktale that Wasila is the girl who fills the dry wadi bed with her tears, making the flood or sayl.

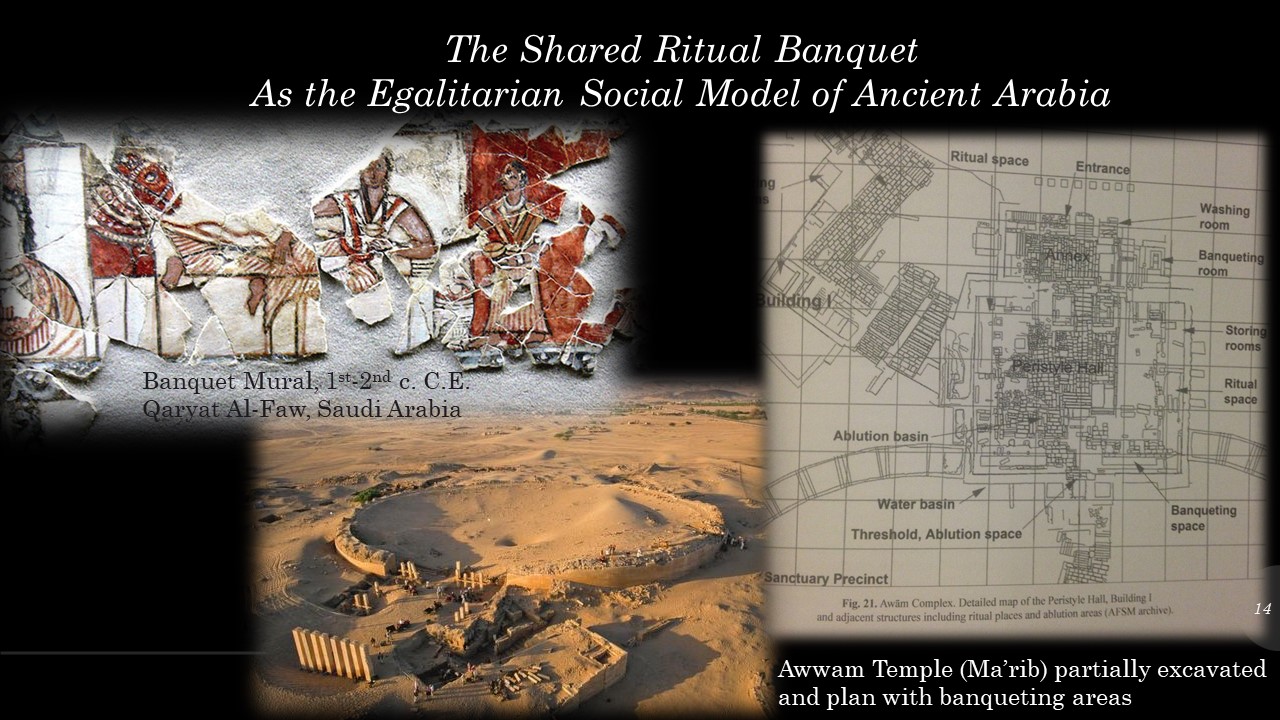

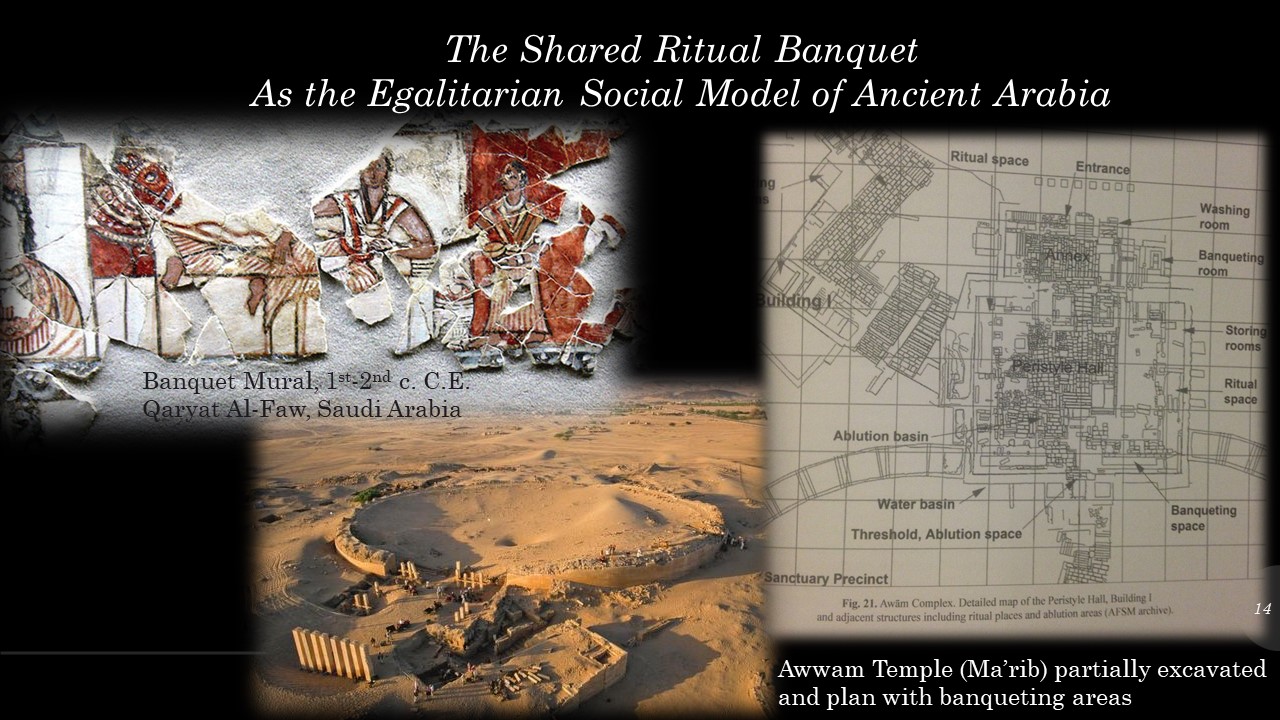

That ritual banquet, celebrated with all the enthusiasm of a marriage feast and the gravitas befitting its divine honorees, will constitute our final comment on the characteristics and continuation of South Arabian social and religious customs from antiquity through Islam. One painted banquet scene is known: a ca. first- or second-century C.E. mural from the site of Qaryat Al-Faw in Saudi Arabia. Furniture and architecture associated with the banquet however appear much more frequently at archaeological sites.[1] The Sabaean ritual banquets following, presumably, a parallel ibex hunt in north Yemen in the vicinity of Jabal Al-Lawdh have been recognized in scholarships for their political currency in uniting the tribes and pledging their support to the Sabaean king in the early centuries before the common era; however, the socially-cohesive role of these ceremonial banquets following the hunt of a wild ibex or the slaughter of a sacrificial bull can be understood on the more individual level between community members, among the nomadic Bedouin and settled agrarian communities alike. Among the numerous idols described by Al-Kalbi, the generous sharing a slaughtered animal is accorded the imperative of a sacrament,[2] and the communal rendering of all aspects of produce- fruits, grains, dates, cattle, etc.- figures into another pre-Islamic figure’s worship, specifically that of ‘Amm-Anas. Here a reproduction of Al-Kalbi’s text is valuable because through its Islamic lens which condemns the consumption of the divinity’s food by its people, it reveals the essential property-transfer of livestock to the divinity which Daum and others have written about in the ancient Sabaean context:

They were wont to set apart a portion of their livestock property and land products and give one part to it and the other to God. Whatever portion of the part allotted to ‘Amm-Anas made its way to the part set aside for God they would restore to the idol; but whatever portion of the part consecrated to God made its way to the part allotted to the idol they would leave to the idol…Moreover they set apart a portion of the fruits and cattle which he hath produced and say, ‘This is for God’- so deem they – ‘And these for our associates.’ But that which is for these associates of theirs, cometh not to God; yet that which is for God, cometh to their associates.

Ill do they judge. [3]

The communal nature of the ritual sacrifice, in this case the aqira specifically, is reinforced with an observation made in the early twentieth century, before this practice had disappeared at Qabr Hud, that no man eats the bull which he gives; all donations to the divinity (in this case Hud) become his property, which he then bestows upon the gathered pilgrims.[4] The emphasis that all eat equally, rather than in proportion to their donation, underlines the egalitarian ideal which these ritual banquets upheld for Arabian society through time. We also possess inscriptional evidence from the Awwam Temple of Ma’rib that sacrifice could required if the boundaries of sacred space, called a mwtn or gwr in Sabaic penitential inscriptions, were transgressed,[5] and an episode of just such a transgression is detailed in Al-Kalbi’s account of the ultimate rejection of the worship of an idol, in this case Al-Fals.[6]

[1] For the plan and dedicated banquet-spaces at Awwam, see Maraqten, 125.

[2] “When thou meetest two black shepherds with their sheep, / Solemnly swear by Nuhm, / With shreds of flesh between them divided, / Go thy way; let not gluttony prevail.” Al-Kalbi, 35.

[3] Al-Kalbi, 37-38.

[4] Daum, 61.

[5] See Maraqten, 110.

[6] Al-Kalbi, 51-52.

Here ends the overview of some but by no means all of the salient characteristics of worship in pre-Islamic Arabia and particularly those of the southern edge of the peninsula’s vibrant and advanced civilizations in antiquity. Much more could be said on the subject; the inscriptions of Awwam marking sacred space and calling for physical as well as ritual purity we very well may draw an anthropological trait-d’union to Islamic wudu rituals undertaken before entry into a mosque’s sacred space. The sculpture from Dedan and the Lihyannite dynasty in antiquity also line up with Al-Kalbi’s Biblical time-line which was introduced next to the carved stones of the bronze age in the beginning of this study. A great deal of the various idols mentioned by Al-Kalbi have proliferated in the most recent translations of Sabaic and ancient South Arabian epigraphy, and any one of those instances is a worthwhile study of its own. These are, however, far beyond the present scope of this paper which was to shed light on the period and culture from which emerged the Prophet Mohammed and the Islam which proclaimed to erase all that had come before. As we have seen in more than a few instances, not everything was erased completely, and the work of historians and anthropologists in bringing to light the picture of Arabian society and religion on the eve of Islam makes possible a fuller appreciation of the true scope of the revolution of the new religion from the seventh century forwards in Arabia and beyond.