13. The Art of Himyar and the Mountain Kingdoms of Yemen

Historians of pre-Islamic South Arabia have divided its ancient history into two broad historical periods: the Caravan Kingdoms of Saba, Qataban, Awsan, Ma’in, Hadhramawt, and more minor powers were those whose power and wealth derived from the overland frankincense transport through the first century B.C.; the later Mountain Kingdoms, including the Himyarite Kingdom which would be South Arabia’s last great native power before the advent of Islam, rose to power in the highlands of what is now Yemen on part of its successful control of a lucrative sea-trade route with Greeks, Romans, and other Mediterranean traders as well as with the kingdoms of the Indian Ocean to the east.

We recall that the kingdom of Ma’in in the northwest of what is now Yemen produced artwork from around the eighth century B.C. that was startling similar to early Sumerian artwork. The Minaean Kingdom existed as a separate entity from its more powerful neighbor Saba to the south; from the fourth century B.C. to the first century C.E., Ma’in was known to Greek and Roman writers for their monopoly on the perfume trade and, at an early date, the lucrative incense trade. The wide range of the Minaeans’ trade networks is testified to by references to this people on an Egyptian sarcophagus from the Ptolemaic era and in a dedication on an altar on the island of Delos. These fabled riches were the lure which prompted the emperor Octavian Augustus to send Aelius Gallus, the Prefect of Egypt, on Rome’s first and last military campaign into Arabia Felix. In 24 B.C., the Roman army successfully took first Najran, then the Minaean city Yathil, which they called Yathrula and today is called Baraqish, but archaeologists have argued that the Minaean civilization by then was in a marked decline. The last Minaean inscriptions from the area are dated to around 100 B.C, and the last mention of M’ain in a Sabaean inscription is from a few decades prior to the Roman expedition. Unsatisfied by their hollow conquest of the once-great trading kingdom of Ma’in, the Roman army pushed forward into the desert towards Marib, the capital of the fabled Sabaean Kingdom. However the Roman expedition’s forces, were no match for either the uncompromising terrain of South Arabia nor the expert stone-masonry of the Sabaean defenses they encountered at Marib. After attempting to lay siege to its fortress-like walls for six days, they conceded defeat and turned back, with only a relative handful surviving the disastrous campaign in Arabia to tell the tale.

Rome certainly hadn’t been the first Western power to dream of capturing the riches of Arabia for their own. At the time of Alexander the Great, Greek ships scouted the Persian Gulf and around the South Arabian coast with a future military campaign in mind, but Alexander died of a fever before this next phase of conquest could be realized. These expeditions from the fourth century B.C. onwards however developed a trade route which would transform the networks of power and patronage on the interior of the Arabian Peninsula. An anonymous Greek sea captain wrote The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea in the first century C.E. which furnishes the extensive and detailed nautical knowledge Greek and Mediterranean traders had at hand of the Red Sea and Arabian Sea coastlines as well as their ports, their markets, and their people.

With this brisk maritime traffic came contact, trade, influence (even though Arabia isn’t typically included in maps of Hellenistic influence), and ultimately transformation. The artwork of South Arabian kingdoms from the late third century B.C. onwards shows its unmistakable marks, and traditional centers of power would find themselves eclipsed by different tribes with a more direct access to the coastline. The Kingdom of Qataban was one of the most wealthy and powerful of the old Caravan Kingdoms from at least the seventh century B.C. onwards, but at the height of its power around the third century B.C., Qatabanian sovereigns adopted coins with the owl motif typical of Athenian currency. At Timna, the capital city of a vast administration, we find an identical motif at a Qatabanian villa as we do at Roman Pompeii. Specifically, a pair of bronze lions mounted by what appears to be Cupid recalls the motif of Cupid riding a Lion (or alternately, Dionysos riding a Tiger) which dates to the late second century from the Villa of the Faun at Pompeii. However, in spite of Qataban’s cosmopolitan character and wealth derived from the caravan routes it had established- in some cases, cutting smooth roads out of the rock surface in a method reminiscent of the Romans’ administrative style- by the first century B.C., Qataban (and the other ancient kingdoms reliant on the overland trade routes) were in crisis.

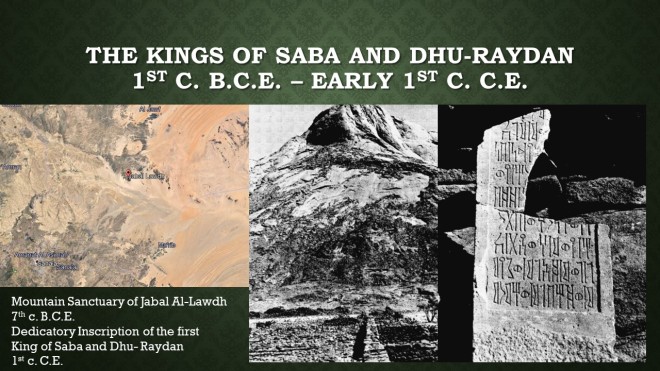

As sea trade dominated trade and disrupted the older overland route, the political structure of the Sabaean kingdom changed dramatically. In our last lecture, we have seen how the very oldest rulers of Saba called themselves the mukarribs, and these have been theorized to have been closer to a priest-king identity. With the first malik, or king, of Saba, the role of its rulers became more concerned with the administration of taxes, infrastructure, and trade. With the rise in the commercial maritime kingdoms, new strongholds appeared in the highlands of the mountains along the southwest corner of the Arabian Peninsula, and Sabaean titles reflect this new power-sharing arrangement; we have entered the period of the Kings of Saba and Dhu-Raydan. Whereas Saba remained the ancient capital at what is now Marib, Dhu-Raydan was the name of a later mountain-fortress which became both symbol and synonym for their power. The spiritual legitimacy of this new arrangement was underscored by the first South Arabian kings to use this title by returning to an ancient ritual site of the seventh-century ruler Karib’il Watar, also called Karib’il the Great, considered to be Saba’s last mukarrib and first malik. In line with South Arabian convention, the temple site was called the Ka’ab, a name still in use for the principal shrine of Islam at Mecca. This mountain sanctuary, located at Jebal al-Lawdh at the entrance to the Jawf valley from the north, had been left neglected for centuries, but at a time of crisis and transformation when the Sabaean rulers were keen to extend their power further into the highlands, and by extension to the lucrative sea-ports on the Red Sea, the first “King of Saba and Dhu-Raydan” revitalized the temple sanctuary’s ritual use and left voluminous inscriptions of his feats. Specifically, this first king, Dhamar’ali Watar Yuhan’im, revived the tradition of Karib’il the Great’s ritual banquet and a pact solemnly sworn by the Sabaean federation of tribes. As political moves, these shored up critical support in uncertain times.

In ancient Sabaic, “Dhu” is a title roughly equivalent to lord. So what exactly was implied by this new title, the “Lord of Raydan”? Raydan was the name of a great fortress and state palace erected at Zafar, the new center of power in the mountains with direct access and control of the sea trade. Zafar was the stronghold of the up-and-coming Himyarite Kingdom, whose power would eventually eclipse that of Saba, Qataban, and others and would rule a unified Yemen for some time until the Abyssinian invasion of the sixth century C.E. It is a fascinating relic that the title of the Kings of Zafar, sometimes written as Tafar, in Arabic- ra’is Tafar appears to have taken on a new life as the pre-regnal title “Rastafari” given to Haile Selassie of Ethiopia before the 1930’s and the spiritual movement which developed under his persona. Nevertheless, among the ruins of Zafar in Yemen, the fortress Raydan is almost entirely vanished, but an eighteenth-century sketch preserves a view of a more intact state.

The Hellenistic-influenced murals from Qaryat Al-Faw farther north in Arabia provide the oldest depiction of typical Yemeni architecture, as relevant today as for mountain kingdoms from the first century C.E. onwards: the Tower Palace. A central staircase, sometimes multiple, provides access to often labyrinthine series of rooms and floors above. These were rigorously vertical structures, with thick impenetrable walls at the base giving way to the light and airily-decorated floors above. At the very top is the mafraj, a kind of Yemeni penthouse which served as the preferred room of Himyarite kings and contemporary Sanaanis alike for receiving guests. The white plaster which gives the Yemeni Tower Palace its gingerbread look characteristically frames the qamariyahs, or stained-glass windows. On the floor level, small windows could provide ventilation. Whereas we can see in the Qaryat Al-Faw mural faces peeking out from the Tower Palace’s many floors, this is the artist’s convention to show that the palace is inhabited; the practical architecture of Yemeni Tower Palaces is intended to obscure the view of its inhabitants from passers-by on the street. Wood window-boxes preserve this privacy in otherwise open windows, or sometimes thin alabaster panes are employed which let light in but otherwise present an opaque surface to the outside. The Old City of Sana’a preserves the greatest concentration of ancient tower palaces; as a UNESCO Heritage Site, it has been commonly remarked that some of Sana’a’s architecture could be as much as 1,000 years old. The Qaryat Al-Faw mural from the first or second century C.E. revises that estimate of the type by another thousand years, though individual palaces have been repaired and rebuilt many times as need dictates. Particularly at the present moment, Sana’a and its ancient tower palaces have been under heavy bombardment by the Saudi-led coalition in the ongoing war since 2015, so awareness and preservation of this ancient type of Yemeni architecture will be of paramount importance in the years to come.

Yemen’s oldest, largest, and perhaps most famous tower palace was not in Zafar however. Even in satellite images, the footprint of Ghumdan Palace (also called Castle, interchangeably) dwarfs those of its surrounding modern descendants in the modern capitol Sana’a. It was razed in the seventh century C.E. by the orthodox Islamic caliph Uthman ibn-Affan, but its fame persisted in the tenth-century writings of the Medieval Yemenite historian Al-Hamdani. Verses of poetry preserve its most spectacular features: twenty floors which reached the clouds, a façade wrought in marble and precious stones, a copper roof, eagles and roaring lions which harnessed the power of wind, and even a clepsydra device. Where nothing physically remains, the poetry nevertheless paints a picture of a not only a feat of engineering to rival any of the other wonders of the ancient world, but also the integration of technology which harnessed wind and water we have seen emerge from Hellenistic Egypt. Modern historians have dated the foundation of Sana’a and Ghumdan Palace to the rise of the Mountain Kingdoms of Yemen by the first century C.E., but the Medieval Yemenite historian Al-Hamdani repeats the legend (still fondly told in modern Sana’a) that the foundation for Ghumdan Palace was laid by Shem, the son of Noah, but even in the tenth century this beloved story is tempered by the attribution of Ghumdan’s construction to the Sabaean-Himyarite king Ili-Sharha Yahdib, which in the chronology of the historian Alessandro De Maigret, would place it in the early first century C.E. Both Medieval and modern sources tentatively agree that Ghumdan Palace’s construction and the foundation of Sana’a predate the later Raydan Palace at Zafar which would come to symbolize the Himyarite Kingdom itself.

The foundation of the Himyarite era has been fixed solidly to the year 110 B.C.; historians arrived at this date from later rock-carved inscriptions describing the military campaign of a Himyarite ruler whose dates were already known. Therefore, the Himyarite dating employed- year 633 of the Himyarite Era in this case- could be traced back to arrive at this late second-century B.C. foundational date. For the first three centuries of the common era, no trace of a “King of Himyar” is found; instead, the Himyarites appear as tribal leaders, and the title of king is reserved for the new, composite identity the Sabaean kingdom had assumed. It has been theorized that the old, powerful trading kingdom of Qataban coalesced after its destruction under the banner of Himyar to again repel and ultimately rival Sabaean dominance on the South Arabian Peninsula. By the late first century C.E., the Himyarite Kingdom controlled most of its ports, including Eudaemon Arabia, the ancestor of modern-day Aden, and a distinct style of writing begins to appear on monumental bronze tablets proclaiming the achievements of Himyar rulers. With their virtual monopoly on the sea trade, we see currents from the larger world revolutionize the appearance of ritual and funerary artwork from Zafar and the lands of Himyar. A strikingly naturalistic hand votive is a dramatic departure from the previously, abstract hand-votives such as the sketchily-dated South Arabian bronze hand in the Louvre referenced in the Red List of Yemeni Antiquities released this year by ICOM. The influence of Hellenistic sculpture upon the Zafar hand is readily apparent, yet it preserves traditional elements of South Arabian religion as well. In this vein, as on much older votive sculpture, we find a dedicatory inscription of the hand by an identified individual, in this case a Wahab Ta’lab, marking the donation of this votive object for his deceased patron. Funerary observances continue to be the principal driving motive for the creation and dedication of artwork in the Mountain Kingdoms of Yemen as it was for the Caravan Kingdoms of more distant antiquity.

The Era of Himyar also marks a decisive shift in the art history of Yemen. Whereas the kingdoms of Saba, Qataban, and other powers which thrived on the overland trade routes typically preferred highly stylized, to-a-degree abstract renditions of people and animals deployed as decorative elements along the pediments of temples, doors, ritual furniture, and other surfaces, the era of Himyar ushers in forms which before had been unknown in Arabia. The grape leaf and vine motif, for example, is another Hellenistic import conceptually which was adapted by South Arabian carvers to suit their taste for the stylized decoration of surfaces. In this carved panel found at Bayt Al-Ashwal, the modern village which sits over some of the ruins of ancient Zafar, we see the Hellenistic motif given the repetitive and stylized treatment we have come to associate with the South Arabian aesthetic sense. The Corinthian column capitol, or some derivative of it, also begins to appear in both the art and architecture of the Himyar Era. The Sana’a Museum holds two carved capitals with prominent acanthus leaf designs which are echoed in the column depicted on a relief fragment from Zafar. This fragment is also intriguing for its depiction of a leopard, an animal considered to have once been indigenous on the Arabian Peninsula but which has not featured in South Arabian artwork. It appears that the leopard, indeed any feline with the exception of the composite Arabian lamassu-like creatures derivative of Mesopotamian art, must be categorized another imported theme like the acanthus leaf capitol, the grape vine motif, or even the debateable Dionysus riding a lion sculpture from Timna.

The most dramatic difference in the visual arts under the Himyaritic Era which distanced their material culture from their Sabaean, Qatabanian, and other predecessors in South Arabia was a break from the seemingly rigid rules of funerary artwork. In the case of the Sabaeans, funerary stele featured simple, centrally-oriented motifs: a head, a bull’s head or other animal’s, a hand, or even just two eyes.

In the case of Qataban however, we see the stirrings of a figurative style that would go on to define Himyarite funerary markers; more compelling for this hypothetical link is the idea of De Maigret’s that the tribes of Qataban, after the neighboring rival kingdom of Hadhramawt had set fire to its capital Timna and dispersed its ancient centers of power, had coalesced under the banner of Himyar to oppose Saba and Hadhramawt in the first centuries of the common era. This kind of funerary stela which is exclusive to the Qatabanian civilization is the Dhat Himyam type, which gets its name from the presumption that its characteristic image depicts a goddess (dhat is the feminine equivalent of dhu, or the equivalent of “lady” to its “lord”) although others have argued convincingly that it shows the deceased assimilated to an iconographic type (a phenomenon which is known to have occurred in Greek art, for example) or perhaps a priestess or member of an otherwise elite caste of society (which is supported by the absence of the father’s name and the uncommon presence of the mother’s name instead, a convention common to South Arabian priestess traditions). Regardless of its central female figure’s precise identity, the Dhat Himyam markers anticipate more than any other pre-Himyarite style the direction in which later Himyarite funerary markers will go. The Dhat Himyam markers ubiquitously feature a single woman’s figure from the torso up that is raising its right hand and clutching a sheaf of wheat with its left. These figures are carved in relief from the marble or alabaster base in degrees ranging from low to high depending on whether it is an early or a late example; similarly, the attention paid to the rendering of the linen’s texture of her clothing or to the details her jewelry is commensurate with the individual piece’s early or late dating. In stark contrast to the Sabaean funerary markers we just looked at, the Qatabanian Dhat Himyam type is the first indication of a more fully representational tradition of relief work in funerary monuments which would be transformed in the subsequent era.

Himyaritic funerary markers have experienced a sea-change both in terms of their forms as well as the concepts intended to be communicated. By the second century C.E., we find stele divided into multiple registers- usually two, but sometimes three- which depict scenes from the life of the deceased. This convention calls to mind the funerary markers of non-elite Romans from the time of the early Empire onward; we need only to think of the collection of markers at Ostia, for example, which provide a wide variety of occupations of the average Roman in life and therefore, the correspondingly wide variety of scenes depicting on the markers of their death. We no longer see iconic and generic eyes, a head, or in the special Qatabanian cases the front half of the Dhat Himyam figure, instead for the first time in South Arabian art history, we see scenes unfolding, sometimes within architectural settings sometimes not, which narrate the events and rhythms of life. Multiple figures interact with one another; usually the action revolves around the central figure, assumed to be the deceased. A common type which emerges is the central figure seated (enthroned) with two attendants to either side which calls to mind some of the most ancient types of South Arabian “idols.” The central figure appears to have a kind of musical instrument on its lap, the precise meaning of which remains obscure. The lounging figure on the bottom register is a visual link to the funerary urns and markers of Rome, Etruria, as well as the Phoenicians and other Eastern civilizations as well. Other Himyarite funerary stele feature common activities such as camel-riding, a theme which appears to be associated with warriors’ markers, and what appears to be ritual offerings laid on a table. Another stela shows the use of livestock in agriculture, a staple of Arabia Felix’s fertile highlands. This new concern with the imaging and indeed the immortalizing of the activities of the deceased in life has been rightly surmised to have been the result of contact with the Mediterranean cultures through the maritime trade routes; this “contamination” of South Arabian art has led some historians to class the art of Himyar as a “decadent” phase, but the reimagining of funeral markers by the Mountain Kingdoms of Yemen furnishes far more vivid scenes of life, society, and interpersonal relations than the schematic and stylized stele of the former Sabaean Era.

As has been apparent, frequent warfare and economic competition among the ancient kingdoms of South Arabia led to frequent turmoil and the constant shifting of political alliances as well as boundaries. However, by the late third century C.E., the kingdom of Saba collapsed, Hadhramawt had been conquered, and we can begin to speak of the history of a unified Yemen. The Himyarite Kings by this time had assumed the amalgamated title, “King of Saba and Dhu-Raydan, Hadhramawt, and Yamanat (all of the lands of Yemen).” Whereas we have been careful to use “South Arabia” for this area of the peninsula, now we can begin to call it by its more common designation, in ancient as in modern times, Yemen. After the fourth century, Yemeni society had become politically and administratively unified to an unprecedented degree, but great change was in store in the next centuries. The last Himyarite Kings would adopt Judaism in opposition to their Christian enemies across the Red Sea at Axum (modern-day Ethiopia), and the next centuries of Yemen’s history belong to far broader struggle for supremacy among the monotheistic religions which characterize the Mediterranean, North Africa, and the Arabian Peninsula as a whole. In our next lecture which looks at the earliest artworks of Christian communities of this large region, we will take a look in further detail at some of these events and their reflection in the artworks of the later Himyarite Era.

Bibliography

Avanzini, Alessandra. “The ‘Stèles à la Déesse’: Problems of Interpreting and Dating.” Egitto e Vicino Oriente 27 (2004): 145- 152.

De Maigret, Alessandro. Arabia Felix: An Exploration of the Archaeological History of Yemen. 1996.

Faris, Nabih Amin. The Antiquities of South Arabia being a Translation from the Arabic with Linguistic, Geographic, and Historic Notes of the Eighth Book of Al-Hamdani’s Al-Iklil. 1938

Robin, Christian Julien and Breton, Jean-François. “Le sanctuaire préislamique du Gabal al-Lawd (Nord-Yémen).” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 3 (1982): 590-629.

شكراً كثيراً لهذا البحث المتميز

LikeLike